Scenario Analysis

Lecture

Context and recap

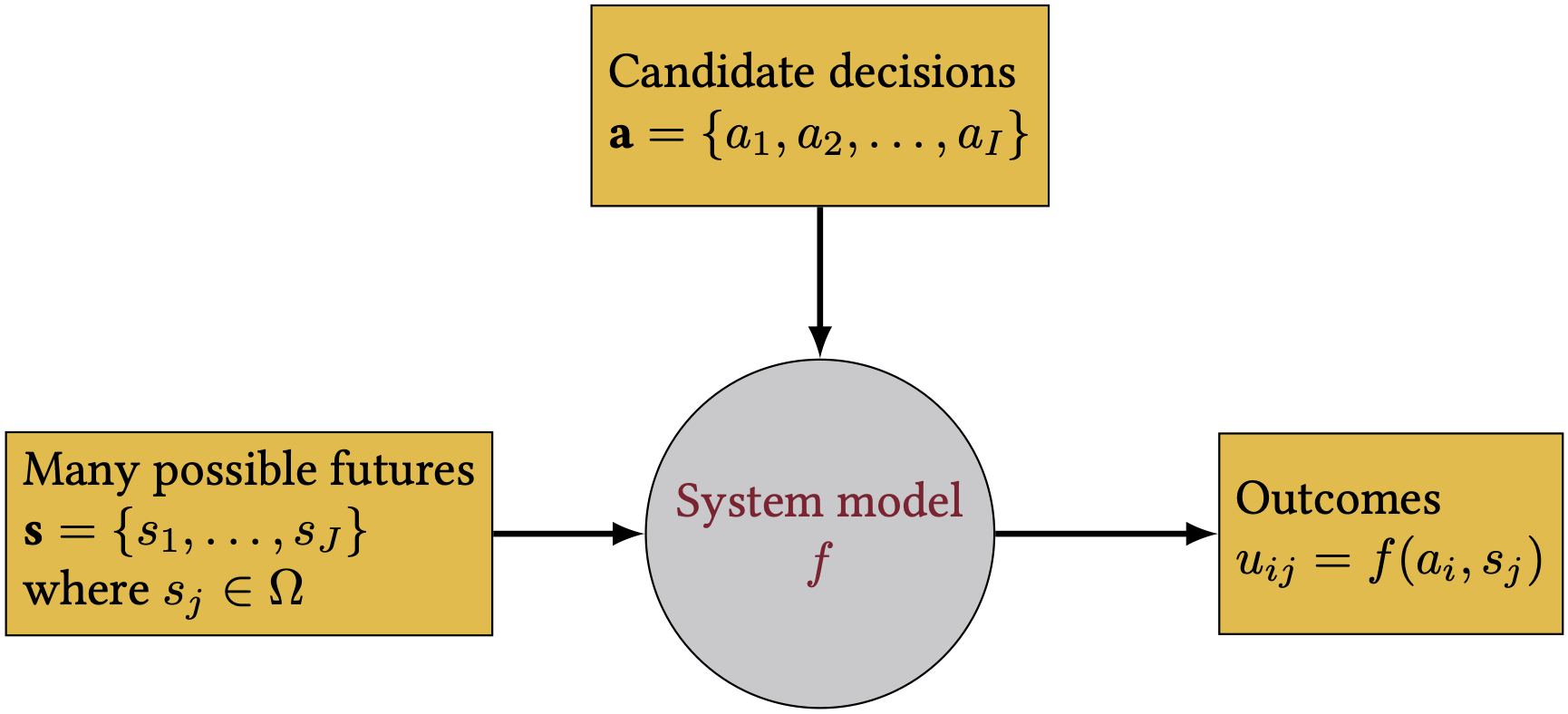

Notation

Let’s tighten our notation just a little bit

- State of the world: encapsulates all inputs to our model.

- Decisions: can be very simple (how high do we elevate a house right now?) or very complex (spatial and/or temporal optimization problems)

- Outcomes: can be a single number (scalar) or a vector if there are multiple outcomes we care about.

Cost-benefit analysis

- Do this for a single state of the world

- Emphasis on discounted cash flow to define “outcomes”

Uncertainty

Uncertainty commonly divided into two broad classes:

- Aleatory uncertainty, or uncertainties resulting from randomness;

- Epistemic uncertainty, or uncertainties resulting from lack of knowledge.

We can also categorize uncertainty based on the source of the uncertainty:

- Parameter uncertainty

- Model structure uncertainty

- External / boundary condition / scenario uncertainty

Uncertainty is represented in models in many different ways. For example:

- Deterministic: hold some things fixed (we always do this!)

- Probabilistic with expectations (lab)

- Probabilistic with sampling

These are all assumptions, and these assumptions can be varied.

Scenario analysis

Scenario analysis is a broad class of methods that are used in many fields. They fall into two very broad categories:

- Stress-testing: pick a few scenarios and make sure the system performs acceptably

- Financial stress testing (Condon, 2021)

- Design storms for flooding

- Traditional scenario analysis: explore several scenarios and see how the system performs

- Optimizing energy systems (see Doss-Gollin et al., 2023 for a critical review 😉)

- Climate science (where RCP scenarios are a key input)

- Often a focus on scenarios that are difficult to put probabilities on

Scenario analysis is a way to explore the consequences of different assumptions. However, decisions that perform well on some scenarios may not perform well on others. Scenario analysis does not attempt to quantify the likelihood of different scenarios. Recall that estimating expectations requires a probability distribution.

Examples

Let’s return to our house elevation problem. What are some things we could consider?

- Sea-level rise: could consider a few different scenarios of sea-level rise (e.g., Sweet et al., 2022)

- Discount rate

Experiment design

- Number of scenarios

- A few = interpretable

- Many = more systematic analysis. Interactions between different sources of uncertainty are important.

- What is a scenario?

- Parameter values

- Model structure

- How to generate / sample scenarios

Wednesday

Grant will lead a discussion of Bankes (1993).

- Emphasis on the “exploratory” nature of the work

- Key insight: iteratively re-frame the problem and generate insight

- Discussion questions are posted.