Equity and Justice

Lecture

Mon., Apr. 1

Uneven exposure to environmental harms

Bullard (1999):

All communities do not receive equal protection. Economics, political clout and race play an important part in sorting out residential amenities and disamenities. Many economically impoverished communities and their inhabitants are exposed to greater health hazards in their homes, in their jobs and in their neighbourhoods when compared to their more affluent counterparts

Question

What examples are you aware of?

You’ve seen headlines like these…

Environmental racism

Bullard (1999):

Environmental racism refers to any environmental policy, practice or directive that differentially affects or disadvantages (whether intended or unintended) individuals, groups or communities based on race or colour.

Question

Why might it be helpful for a framework to focus on proving effect rather than intent?

Today: how to think about equity?

Equity is a complex and multifaceted concept

- Different stakeholders may have varying definitions and understandings of equity

- Despite growing interest in equity, quantitative metrics to measure it are scarce

Most studies that attempt to quantify equity do not clearly explain how their metrics relate to equity

Today’s lecture draws heavily on Pollack et al. (2024).

Getting comfortable with values

Today

Getting comfortable with values

Equity how?

Equity in what?

Equity at what scale?

Equity with respect to what?

Procedural equity

Wrapup

Expectations

- As we discuss topics related to environmental disparities and equity, it’s essential to be kind, respectful, and give each other the benefit of the doubt

- We all have different valuable perspectives and experiences that can contribute to our understanding of these complex issues

- Respectful questioning, dialog, and communication will help us engage with important subject matter

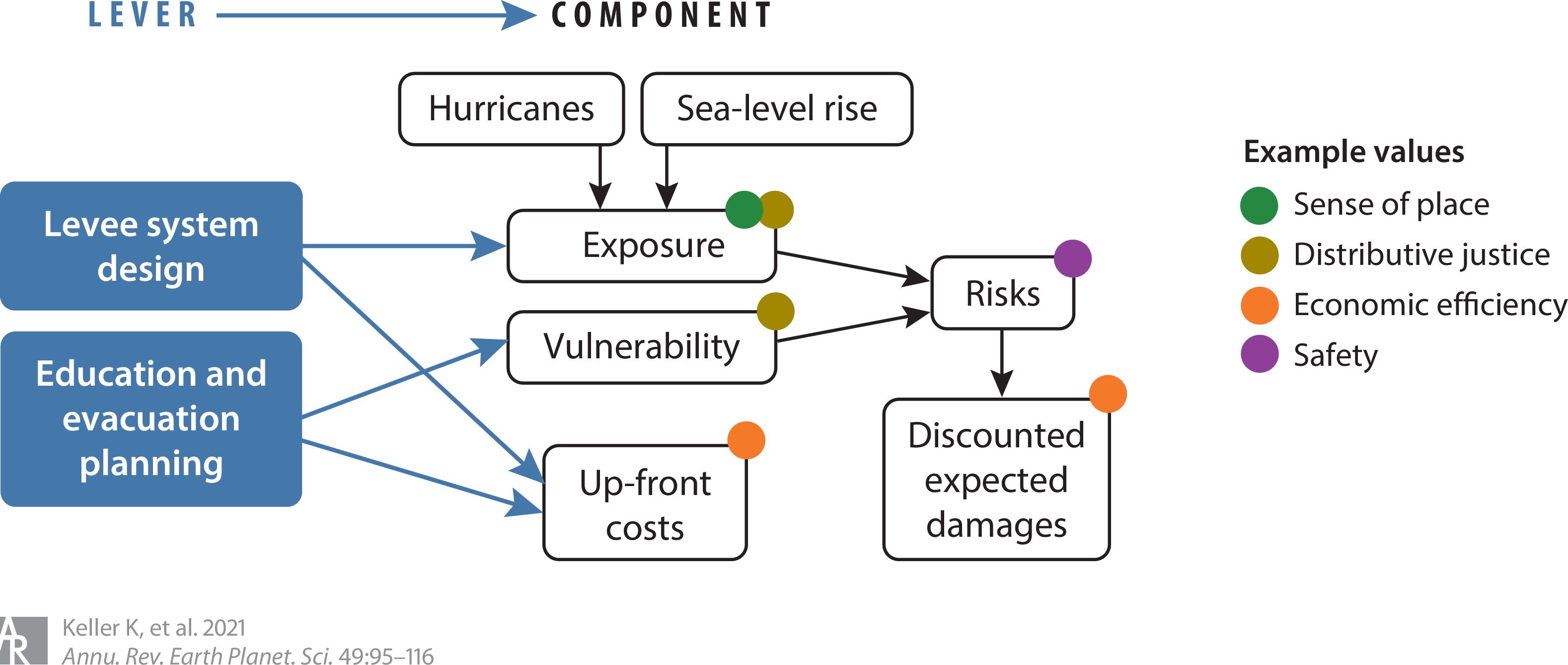

Equity is not the only place where values come into play in climate risk management

Keller et al. (2021)

ASCE code of ethics

asce.org/career-growth/ethics/code-of-ethics

Engineers govern their professional careers on the following fundamental principles:

- create safe, resilient, and sustainable infrastructure;

- treat all persons with respect, dignity, and fairness in a manner that fosters equitable participation without regard to personal identity;

- consider the current and anticipated needs of society; and

- utilize their knowledge and skills to enhance the quality of life for humanity.

tl;dr: engineers apply normative values!

- Honesty / truthfulness

- Benefit society

- Make the profession look good

- Consider diverse societal needs

- Safety

- Confidentialty

We can’t avoid value judgements. However, we should understand them, communicate them, and be open to discussing them.

Equity how?

Today

Getting comfortable with values

Equity how?

Equity in what?

Equity at what scale?

Equity with respect to what?

Procedural equity

Wrapup

Dimensions of justice

Borrowing heavily from Wutich et al. (2023):

- Distributive Justice: Access to resources and outcomes are fair and equitable across social groups and classes (e.g., gender, sexuality, class, race/ethnicity, indigeneity)

- Example: No disparities in flood protection measures between low-income and high-income neighborhoods

- Interpersonal justice: Individuals are treated fairly and equitably, no matter who they are

- Example: Low-income and high-income residents are given equal consideration when applying for post-flood assistance

- Procedural justice: Rules, norms, and decision-making processes are fair and equitable

- Example: All community members have equal opportunities to participate in decision-making processes related to flood risk management

- Recognition justice: Different worldviews and values are fairly and equitably represented

- Example: Indigenous knowledge and perspectives are considered when developing flood risk management strategies

- Transformative (or restorative) justice: Root causes of oppression in systems are collaboratively addressed and communities are peacefully reconstructed

- Example: Historical inequities in flood risk exposure are addressed through targeted investments in disadvantaged communities

Moral frameworks

Table 1 of Jafino et al. (2022) where: \(u(x_i)\), welfare of individual \(i\); \(u(\bar{x})\), average welfare of all individuals; \(\gamma\), inequality aversion factor; \(u(s)\), minimum welfare threshold deemed sufficient; \(w\), preference factor for utilitarianism compared to egalitarianism; \(f(\cdot)\), min-max linear normalization

- Utilitarian: An action should maximize well-being and/or welfare of all affected individuals

- Maximize: \(\sum_{i=1}^n u(x_i)\)

- Strict egalitarian: Equality of outcomes—each individual should have the same level of welfare. An action should strive for such equal distribution of outcomes

- Minimize: \(\max(u(x_i)) - \min(u(x_i))\)

- Rawlsian difference principle: An action should bring benefits for the least advantaged individuals

- Maximize: min(\(u(x_i)\))

- Prioritarian: The outcome of an action is a function of an aggregation of overall welfare with extra weights given to worse-off individuals

- Maximize: \(\frac{1}{1-\gamma} \sum_{i=1}^n u(\frac{u(x_i)}{u(\bar{x})})^{1-\gamma}\) where: \(u(x_i)\), welfare of individual \(i\); \(u(\bar{x})\), average welfare of all individuals; \(\gamma\), inequality aversion factor

- Sufficientarian: An action should ensure that all individuals have secured enough welfare

- Maximize: \(\{i \in n : u(x_i) \geq u(s)\}\) where: \(u(s)\), minimum welfare threshold deemed sufficient

- Envy-free: An action is morally just if no individuals prefer another individual’s achievements and/or welfare

- Minimize: \(\sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=1}^n \max\{u(x_j) - u(x_i), 0\}\)

- Composite principles: The outcome of an action should be evaluated against several moral principles (in this case, between utilitarian and egalitarian)

- Maximize: \(w * f(\sum_{i=1}^n u(x_i)) + (1 - w) * f(\max(u(x_i)) - \min(u(x_i)))\) where: \(w\), preference factor for utilitarianism compared to egalitarianism; \(f(\cdot)\), min-max linear normalization

Caveats

Quantifying a “welfare function” is a notoriously messy problem (Arrow, 1951; Debreu, 1959)

Equity in what?

Today

Getting comfortable with values

Equity how?

Equity in what?

Equity at what scale?

Equity with respect to what?

Procedural equity

Wrapup

Risk assessment outcomes

In the context of flood risk management, several key outcomes are often distinguished:

- Flood hazard: The physical peril or threat of flooding

- Exposure: The people, property, or other assets in the path of potential flooding

- Vulnerability: The susceptibility of exposed elements to damage or harm

- Risk: The potential for consequences, determined by the interactions between hazards, exposures, and vulnerabilities

Outcome measures

Environmental justice theories suggest: examine the distribution of both positive outcomes (benefits, recovery, funding) and burdens (risk) when evaluating equity

- Risk: The distribution of potential consequences across different groups

- Funding: The allocation of resources for flood risk management and recovery

- Recovery: The ability of different groups to recover from flood events

- Benefits: The distribution of positive outcomes, such as reduced flood risk or improved quality of life

Key question

We can measure “equity” in different ways:

- How much investment is given to different individuals / groups?

- How much residual risk remains for different individuals / groups after interventions?

- How much hazard reduction is achieved for different individuals / groups?

- How do these outcomes compare across individuals / groups?

Equity at what scale?

Today

Getting comfortable with values

Equity how?

Equity in what?

Equity at what scale?

Equity with respect to what?

Procedural equity

Wrapup

Why aggregation matters

- The scale and definition of spatial boundaries at which the distribution of an outcome is measured can significantly impact the assessment of equity.

- Aggregating data at different scales can reveal or obscure disparities.

- The choice of aggregation unit should be informed by the specific context and the theories or frameworks being applied.

- It’s important to consider the scale at which inequities are most likely to be produced and experienced.

Common aggregation choices in the literature

Pollack et al. (2024):

- Individual level: Outcomes measured at the individual, household, or building level.

- Neighborhood level: Outcomes measured using community-defined neighborhood boundaries, which are important in many theories of environmental justice.

- Small areas: Outcomes measured using population-based administrative boundaries that approximate neighborhoods, such as census block groups or tracts.

- Large areas: Outcomes measured over relatively large areas like cities or regions.

Equity with respect to what?

Today

Getting comfortable with values

Equity how?

Equity in what?

Equity at what scale?

Equity with respect to what?

Procedural equity

Wrapup

Demographics

- Individual variables, such as income, race, ethnicity, or age

- Aggregated indices that combine multiple demographic characteristics to proxy attributes such as vulnerability or disadvantage

Environmental burden

- Measures of environmental quality, such as access to nature, protection by green infrastructure, or exposure to pollution or other environmental hazards

- Some environmental burdens or goods could also be conceived of as relevant outcomes

Procedural disparities

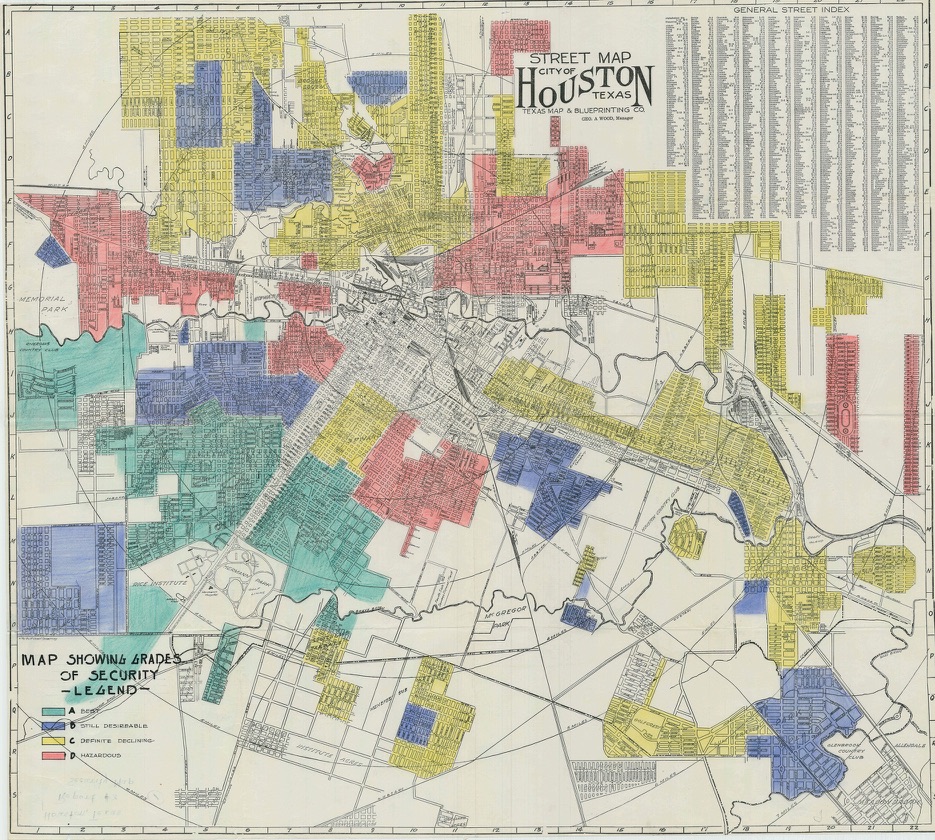

- Discriminatory practices, such as those that produced historically redlined neighborhoods

- Policies that produce distinct groups subject to different procedural factors and experiences

- Example: Insurance claims filed by houses with different sewage systems being treated under different review processes

Causal factors

Theories call for analysts to uncover the causal factors that produce inequities and create injustice, rather than simply describing disparities.

Procedural equity

Today

Getting comfortable with values

Equity how?

Equity in what?

Equity at what scale?

Equity with respect to what?

Procedural equity

Wrapup

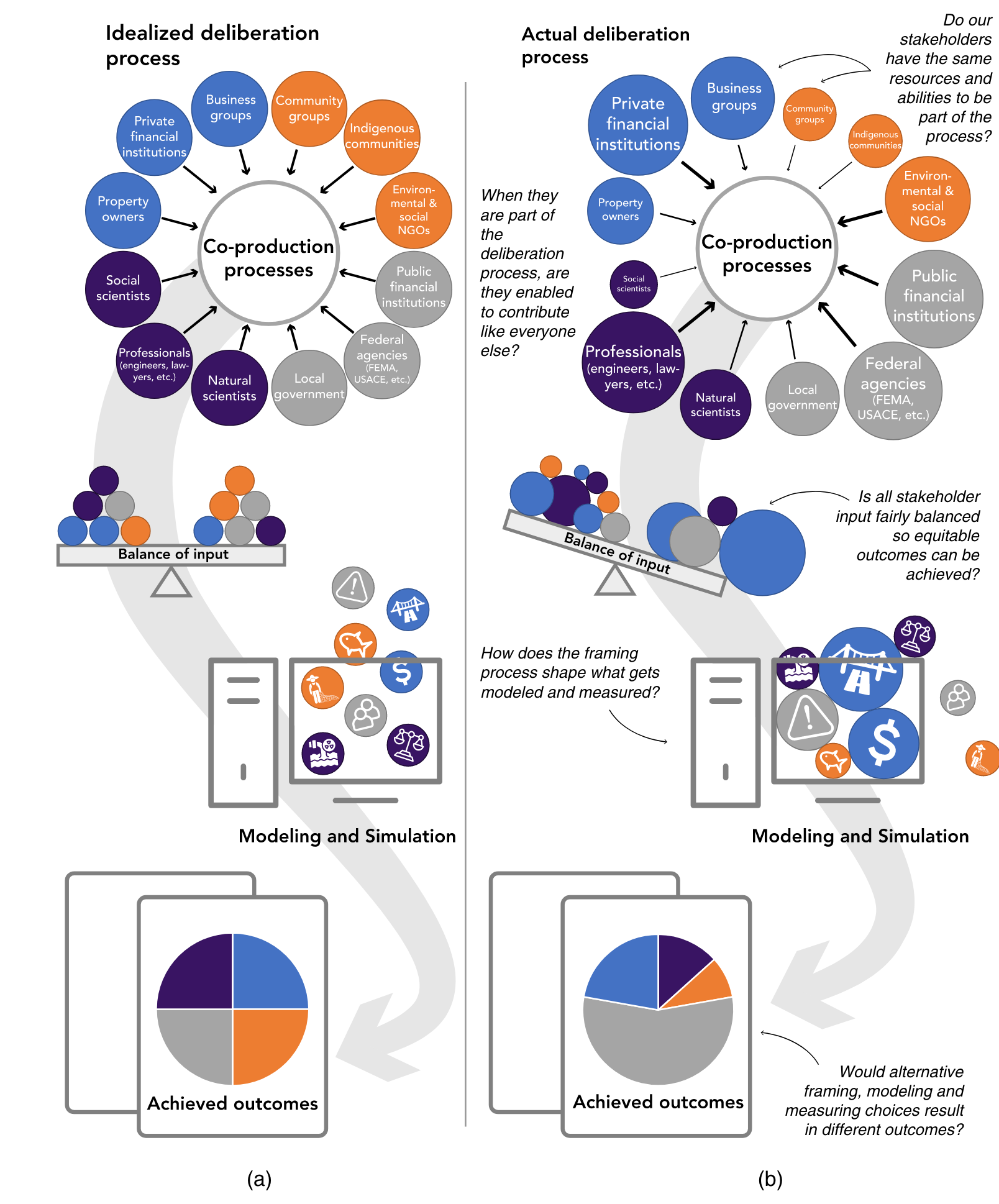

Power dynamics in participatory processes

Fletcher et al. (2022):

- Simply including marginalized communities is not enough; equitable participation is key

- Power imbalances can shape whose knowledge is prioritized and who benefits from the process

- Explicitly identifying power dynamics and finding ways for participants to share power is important

- Skilled facilitation and collaboration with boundary organizations can help address power imbalances

Fletcher et al. (2022)

Wrapup

Today

Getting comfortable with values

Equity how?

Equity in what?

Equity at what scale?

Equity with respect to what?

Procedural equity

Wrapup

Taxonomy

Pollack et al. (2024)

Key points

- There isn’t a single “right” way to quantify equity.

- However, being clear about how you’re conceptualizing and defining equity can help readers determine whether that’s consistent with their values and understanding.

- Grounding equity assessments in theories of justice and local historical context is important.

Wednesday assignment

Rather than reading a paper, please research an environmental injustice in Houston.

- Prepare a two-minute presentation covering the injustice, relying on the key ideas from today’s lecture (e.g., equity in what? across what scale? with respect to what?).

- Upload your presentation to Canvas.

- You may work in mixed undergrad/grad groups of up to three students.

Final projects

We’ll discuss projects in class on Wednesday. Please brainstorm possible topics.