Hazard, Exposure, Vulnerability

Lecture

Wednesday, January 21, 2026

What Is a Fair Insurance Premium?

You own a house in a flood zone.

An insurance company offers you a policy.

How do they decide what to charge you?

Today: The math behind flood risk pricing.

Quick Estimate

A house faces two possible flood scenarios this year:

| Scenario | Probability | Damage |

|---|---|---|

| No flood | 80% | $0 |

| 3 ft flood | 20% | $50,000 |

What’s the expected annual damage?

(30 seconds to think)

Quick Estimate: Answer

\[E[\text{Damage}] = 0.8 \times \$0 + 0.2 \times \$50,000 = \$10,000\]

This simple calculation is the core of risk analysis.

Today: How do we do this when floods and damages are continuous?

Today

- Define key vocabulary: hazard, exposure, vulnerability

- See how these combine to produce risk

- Learn why \(E[f(x)] \neq f(E[x])\) (Jensen’s inequality)

- Introduce Monte Carlo for complex damage functions

Risk Analysis Vocabulary

Today

Risk Analysis Vocabulary

From Components to Risk

Convolution: Hazard → Damages

Extreme Value Theory

The House Elevation Problem

Wrap Up

Hazard

Hazard: The physical event or phenomenon

- Flood depth at a location

- Wind speed during a storm

- Ground shaking from an earthquake

- Extreme temperature

Key insight: Hazards are characterized by probability distributions, not single values.

Exposure: What’s at Risk?

Exposure = assets that could be affected

- Buildings and infrastructure

- People and livelihoods

- Agricultural land

- Economic activity

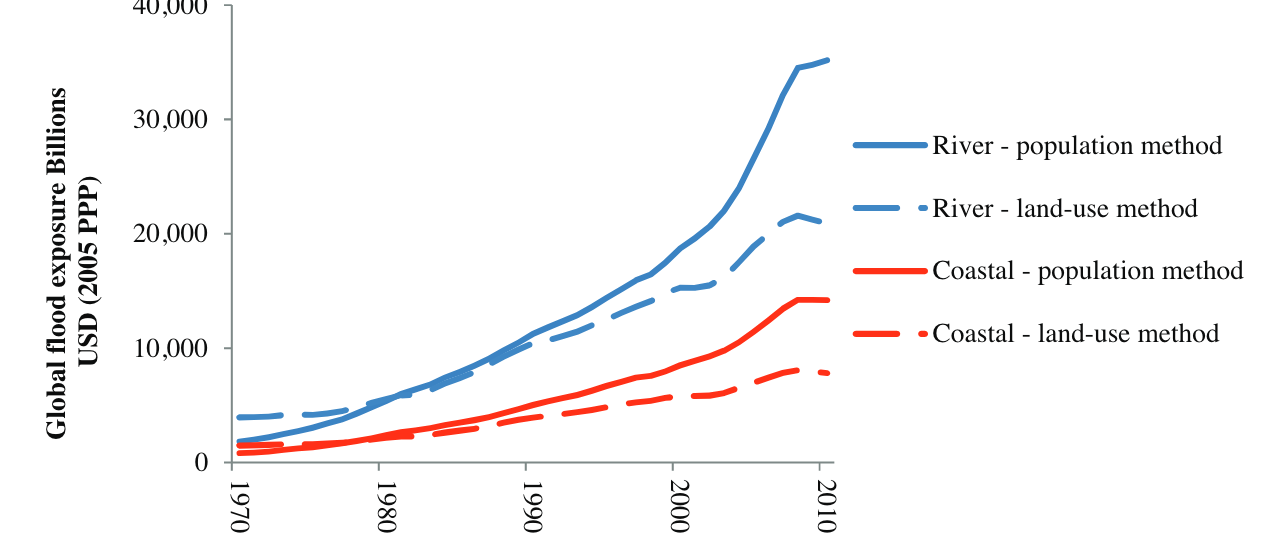

Exposure Changes Over Time

Figure 2: Houston’s built footprint 1800-2018. Development into flood-prone areas increases exposure. Source: Tedesco et al. (2020)

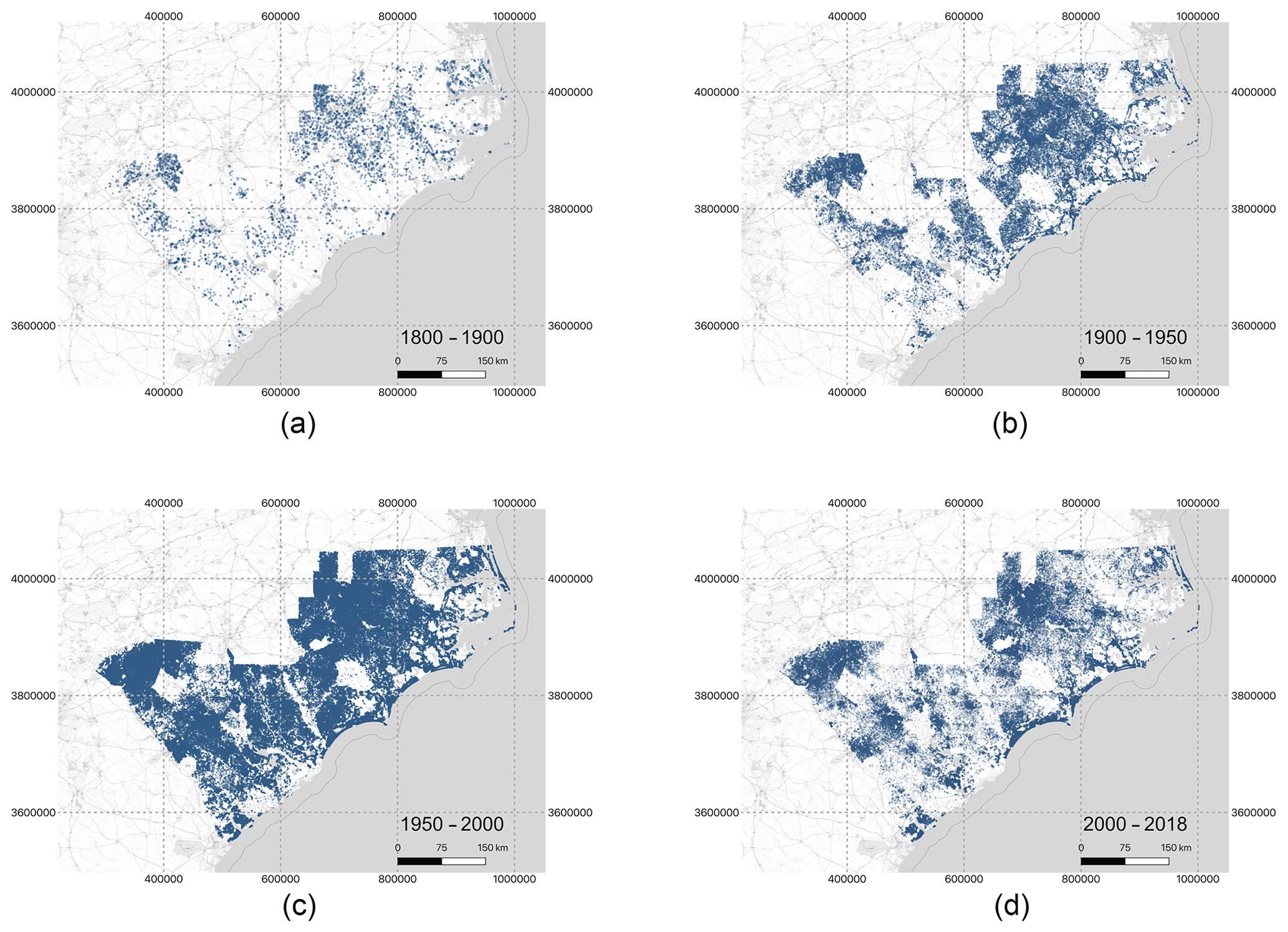

Vulnerability

Vulnerability: Propensity to suffer damage given exposure to hazard

Important distinction:

- Fragility: Probability of failure (binary)

- Vulnerability: Degree of damage (continuous, 0-1)

Fragility vs. Vulnerability

Figure 3: Fragility surfaces (a) and curves (b) show probability of damage given hazard intensity. Source: Gidaris et al. (2017)

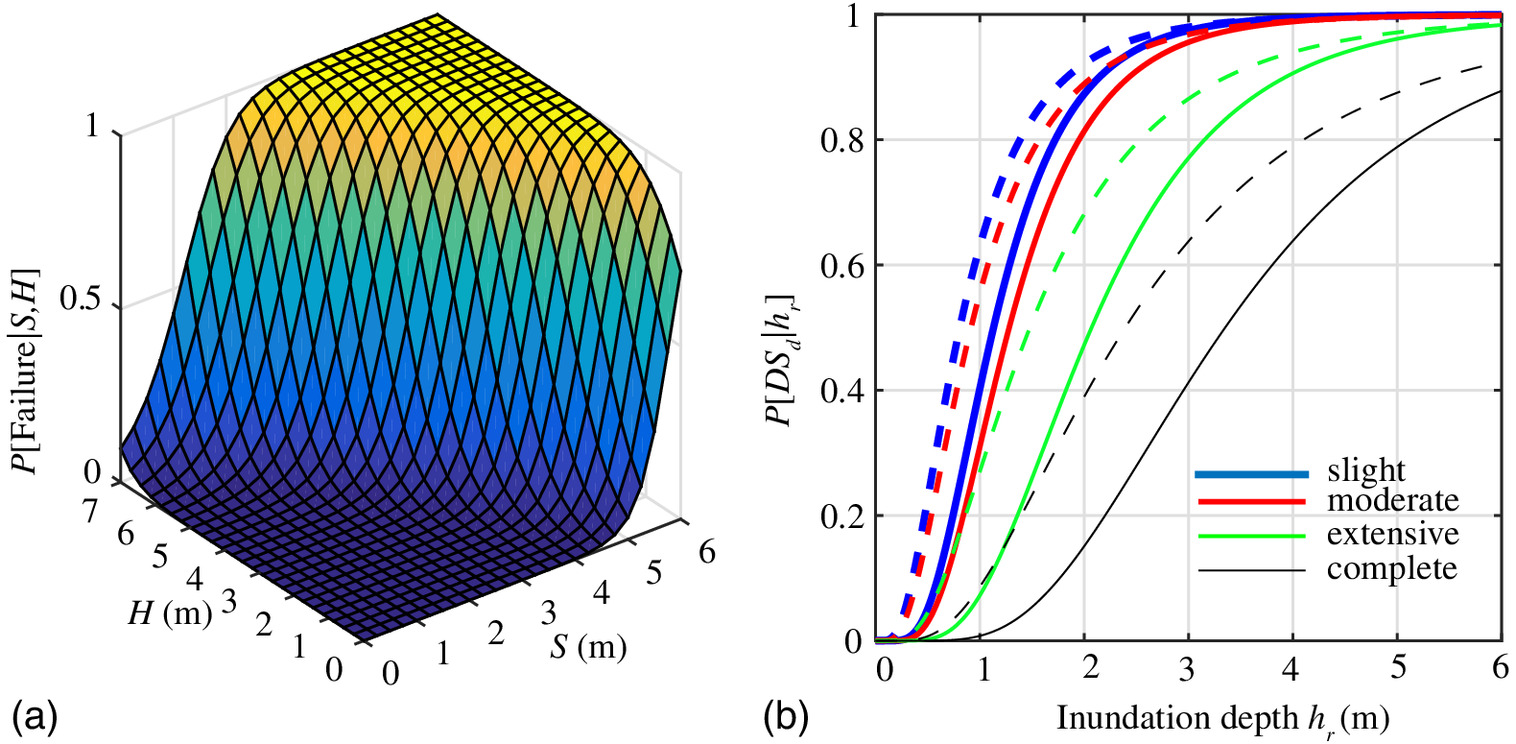

Depth-Damage Functions

For floods, depth-damage functions quantify vulnerability:

Figure 4: Empirical depth-damage from NFIP claims data. Boxplots: Wing et al. (2020) analysis. Lines: USACE engineering curves.

What Do You Notice?

From the depth-damage data:

- Damage increases with depth (obvious)

- Huge uncertainty at any given depth

- Empirical data differs from engineering curves

- First foot of water causes significant damage

From Components to Risk

Today

Risk Analysis Vocabulary

From Components to Risk

Convolution: Hazard → Damages

Extreme Value Theory

The House Elevation Problem

Wrap Up

Risk = f(Hazard, Exposure, Vulnerability)

The fundamental equation:

\[\text{Damage} = \text{Vulnerability}(h) \times \text{Exposure}\]

where \(h\) is the hazard intensity (e.g., flood depth).

For expected damages, we integrate over the hazard distribution:

\[E[\text{Damage}] = \int \text{Vulnerability}(h) \times \text{Exposure} \times p(h) \, dh\]

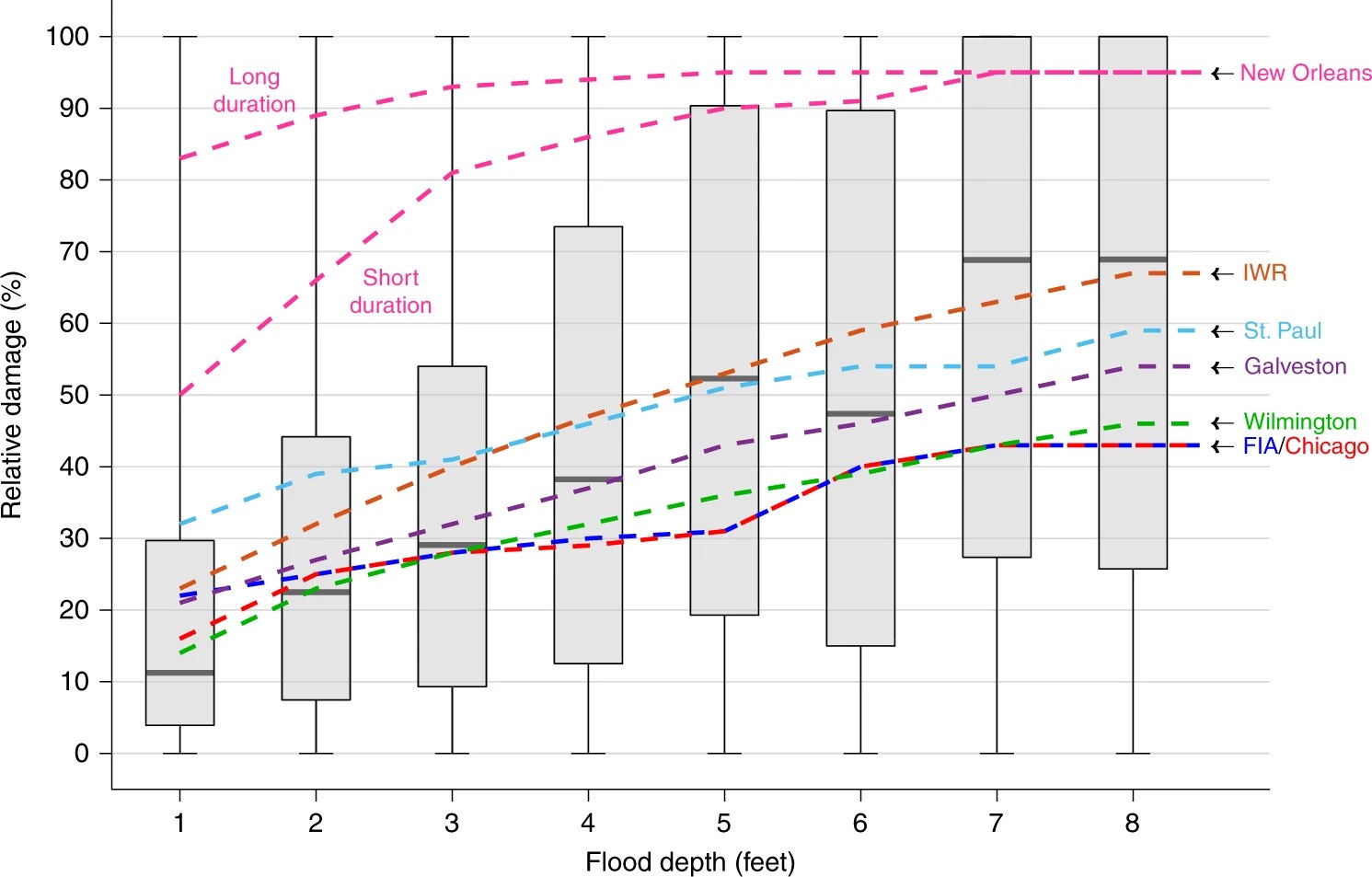

Annual Expected Damages at Scale

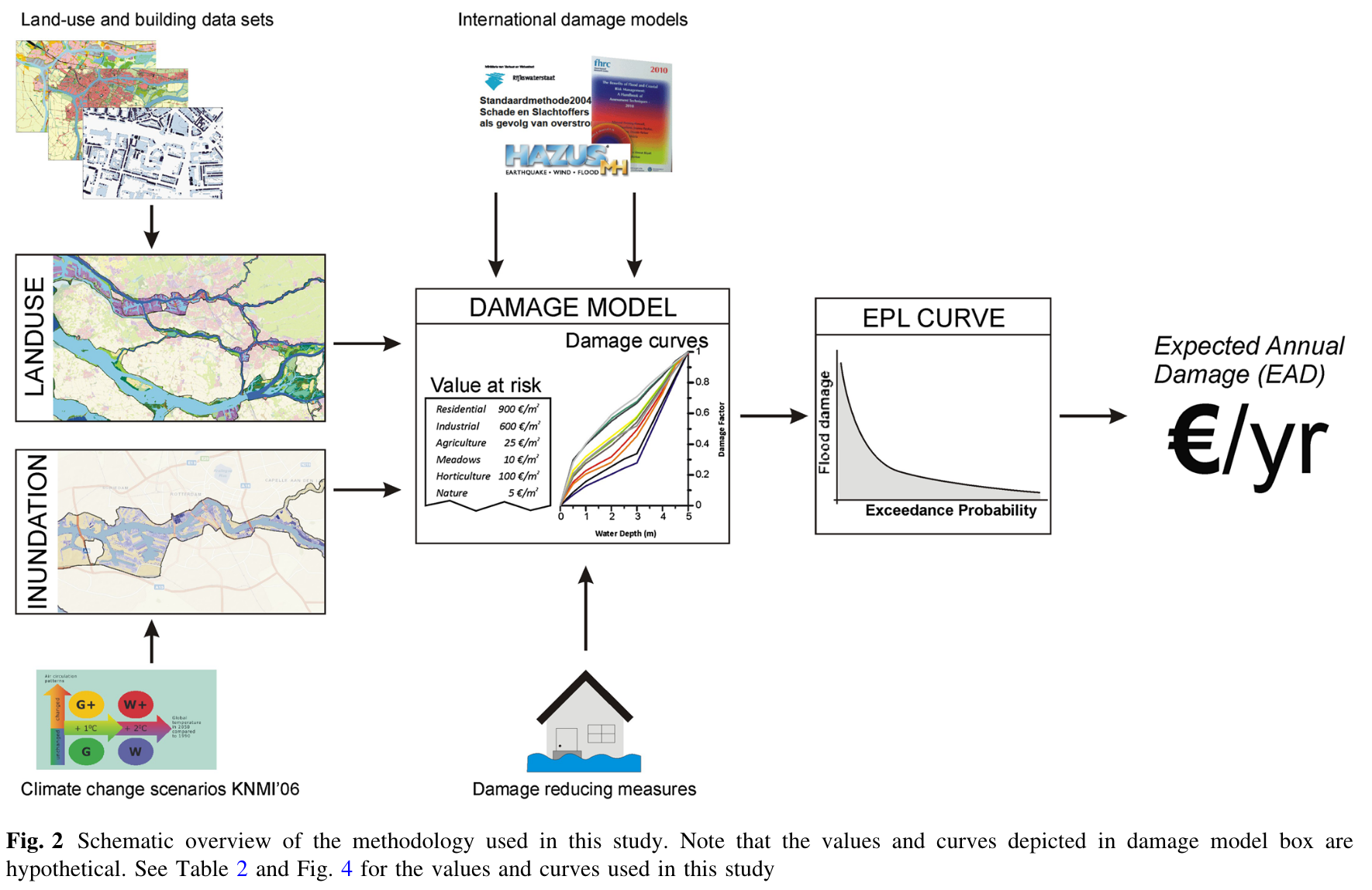

Figure 5: From hazard and exposure data through damage models to expected annual damage (EAD). Source: de Moel et al. (2014)

Your Turn

A city is deciding whether to build a new seawall.

Identify the hazard, exposure, and vulnerability.

Discuss with a neighbor for 60 seconds.

Convolution: Hazard → Damages

Today

Risk Analysis Vocabulary

From Components to Risk

Convolution: Hazard → Damages

Extreme Value Theory

The House Elevation Problem

Wrap Up

The Key Mathematical Idea

We have:

- A hazard distribution \(p(h)\): probability of each flood depth

- A damage function \(D(h)\): damage given flood depth

We want:

- The damage distribution \(p(D)\): probability of each damage level

This transformation is called convolution.

Convolution Illustrated

Hazard Distribution

- 50% chance: no flood (h=0)

- 30% chance: minor flood (h=2ft)

- 20% chance: major flood (h=6ft)

Damage Function

- h=0 → $0 damage

- h=2ft → $10,000 damage

- h=6ft → $100,000 damage

Damage Distribution:

- 50% chance: $0

- 30% chance: $10,000

- 20% chance: $100,000

Expected damage = $0.5(0) + 0.3(10k) + 0.2(100k) = $23,000

Jensen’s Inequality

For any nonlinear function \(f\):

\[E[f(x)] \neq f(E[x])\]

This will be on assessments. Know it.

Jensen’s Inequality: Example

Hazard:

- 50% chance: 2 ft flood

- 50% chance: 8 ft flood

- \(E[h] = 5\) ft

Damage function:

- \(D(2) = \$5,000\)

- \(D(8) = \$90,000\)

- \(D(5) = \$20,000\)

\(D(E[h]) = D(5) = \$20,000\)

\(E[D(h)] = 0.5(\$5k) + 0.5(\$90k) = \$47,500\)

The difference matters: $27,500 underestimate.

Why Monte Carlo?

For continuous distributions, expected damage is an integral:

\[E[D] = \int D(h) \cdot p(h) \, dh\]

This integral is intractable for nontrivial damage functions or probability density functions.

Solution: Monte Carlo integration approximates it with samples.

The Law of Large Numbers

If we draw \(N\) samples \(h_1, h_2, \ldots, h_N\) from \(p(h)\):

\[\frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} D(h_i) \xrightarrow{N \to \infty} E[D]\]

The sample average converges to the true expected value.

More samples → better approximation

Monte Carlo Recipe

- Sample \(N\) flood scenarios from hazard distribution

- Apply damage function: compute \(D(h_i)\) for each

- Summarize the damage samples

Once we have samples, we can compute any statistic:

- Mean (expected annual damage)

- Variance (how much does damage vary year-to-year?)

- Quantiles (what’s the 99th percentile damage?)

This is exactly what you’ll implement on Friday.

Extreme Value Theory

Today

Risk Analysis Vocabulary

From Components to Risk

Convolution: Hazard → Damages

Extreme Value Theory

The House Elevation Problem

Wrap Up

Why Extremes Matter

Most flood damage comes from rare, extreme events.

The problem: Normal distributions underestimate extreme risks.

We need specialized tools for modeling the tails of distributions.

The GEV Distribution

The Generalized Extreme Value (GEV) distribution is designed for annual maxima.

Three parameters:

- \(\mu\) (location): Where the distribution is centered

- \(\sigma\) (scale): How spread out it is

- \(\xi\) (shape): How heavy the tail is

\(\xi > 0\) means fat tails: extreme events are more likely than a normal distribution predicts.

GEV in Practice

In lab on Friday, you will:

- Define a GEV distribution for storm surge

- Sample thousands of possible flood scenarios

- Pass each through a depth-damage function

- Analyze the resulting damage distribution

This is uncertainty quantification in action.

The House Elevation Problem

Today

Risk Analysis Vocabulary

From Components to Risk

Convolution: Hazard → Damages

Extreme Value Theory

The House Elevation Problem

Wrap Up

A Concrete Decision

A homeowner faces a choice:

How high should I elevate my house?

Higher elevation = more upfront cost, but less future flood damage.

The Trade-off

- Elevate 0 feet: No construction cost, high expected damages

- Elevate 14 feet: High construction cost, near-zero damages

- Somewhere in between: ???

Finding the optimal elevation requires:

- A hazard model (GEV distribution for surge)

- A damage model (depth-damage function)

- A cost model (construction costs by elevation)

This Semester’s Sandbox

We’ll use the house elevation problem throughout the course:

| Week | Topic | What We Add |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | Hazard-Damage Convolution | Basic Monte Carlo |

| 3-5 | Risk Metrics | EAD, VaR, CVaR |

| 6-8 | Decision Analysis | Optimal static decisions |

| 10-13 | Deep Uncertainty | Robust optimization |

Wrap Up

Today

Risk Analysis Vocabulary

From Components to Risk

Convolution: Hazard → Damages

Extreme Value Theory

The House Elevation Problem

Wrap Up

Key Takeaways

- Risk emerges from the interaction of hazard, exposure, and vulnerability

- Exposure is growing: More assets in harm’s way

- Convolution transforms hazard distributions into damage distributions

- Monte Carlo lets us handle complex, nonlinear systems

- The house elevation problem gives us a concrete sandbox

Lab Preview: Friday

On Friday, you will:

- Define a GEV distribution for storm surge

- Implement a depth-damage function

- Use Monte Carlo to compute damage distributions

- Extend to 100 houses at varying elevations

- Begin using the SimOptDecisions.jl framework

References

Dr. James Doss-Gollin