Climate Science and Scenarios

Lecture

Monday, January 26, 2026

Motivating Questions

- What causes climate hazards?

- What have we not observed that is still possible?

- How might these pattern change in the future?

The Climate System

Today

The Climate System

What Generates Extremes?

Variability and Persistence

Models and Their Limits

Sea Level Rise

Wrap Up

A Fluid on a Rotating Sphere

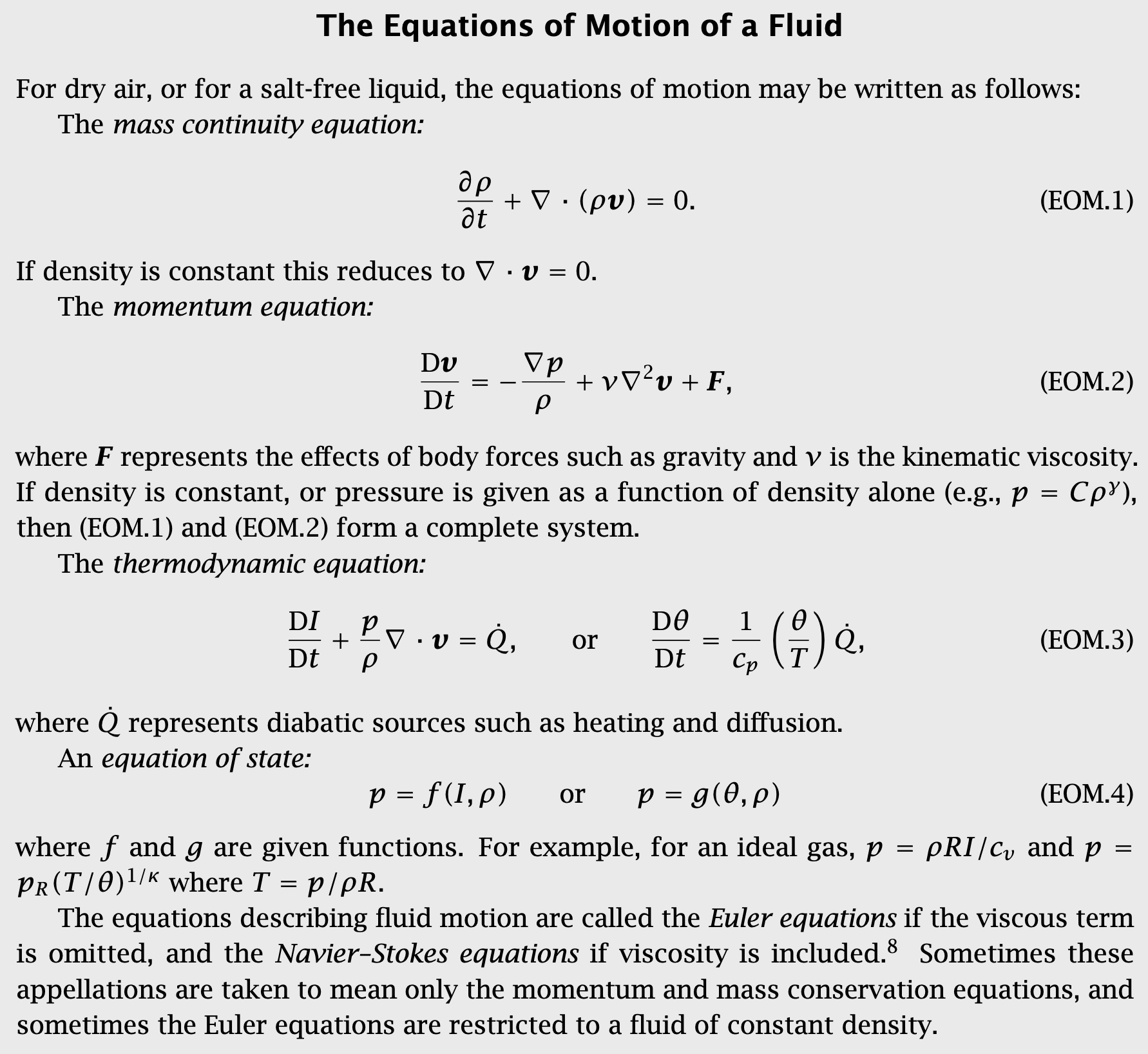

Climate is governed by the Navier-Stokes equations on a rotating sphere, heated unevenly by the sun.

- Conservation of mass, momentum, energy

- Ocean + atmosphere + land + ice + water cycle

- Nonlinear interactions across scales

Equations of Motion

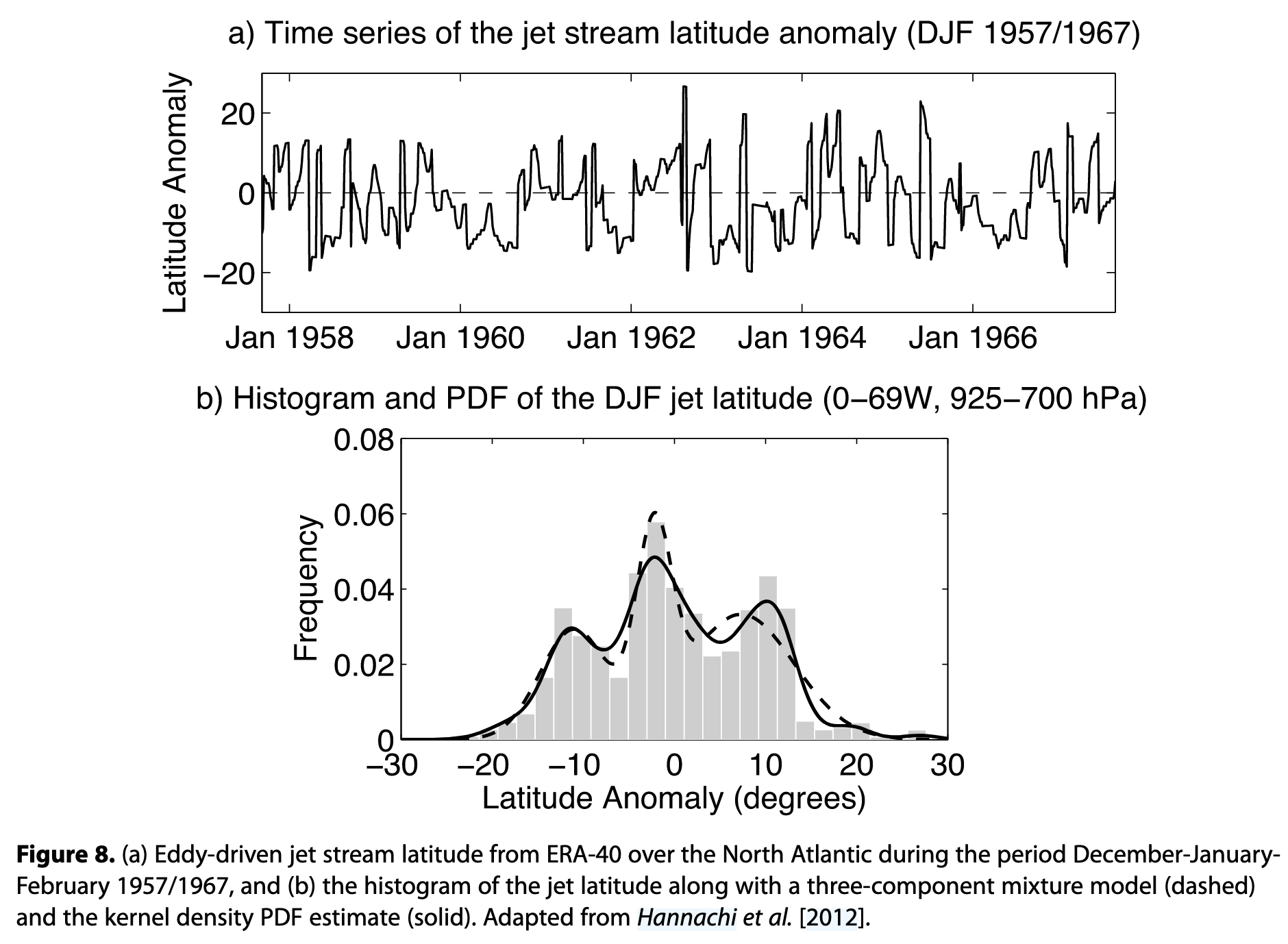

Chaos and regimes

The climate behaves as a nonlinear dynamical system with characteristic modes or regimes.

Weather vs. Climate

Weather Prediction

An initial value problem

- Sensitive to starting conditions

- Errors grow exponentially

- Predictability limit: ~2 weeks

Climate Projection

A boundary value problem

- Driven by energy inputs/outputs

- Shape of the attractor

- Statistics over decades

What This Means for Risk

We cannot predict what the weather will be on January 26, 2100. We can project the statistical properties:

- What temperature will it be on average?

- How likely is it that we get at least 2” of rain?

- What is the probability distribution of maximum wind speeds?

What Generates Extremes?

Today

The Climate System

What Generates Extremes?

Variability and Persistence

Models and Their Limits

Sea Level Rise

Wrap Up

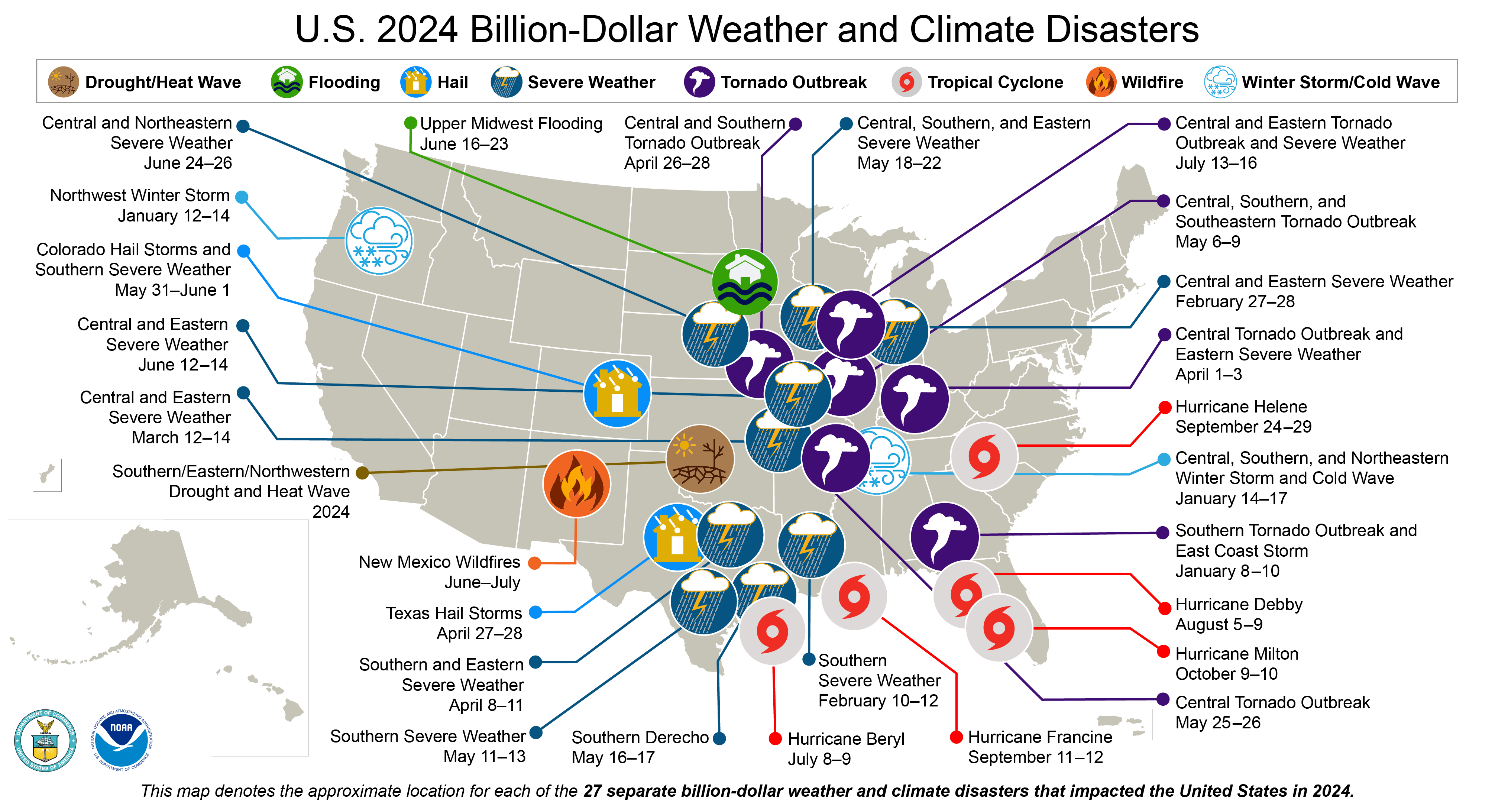

Billion Dollar Disasters

U.S. billion-dollar weather and climate disasters. Source: NOAA NCEI

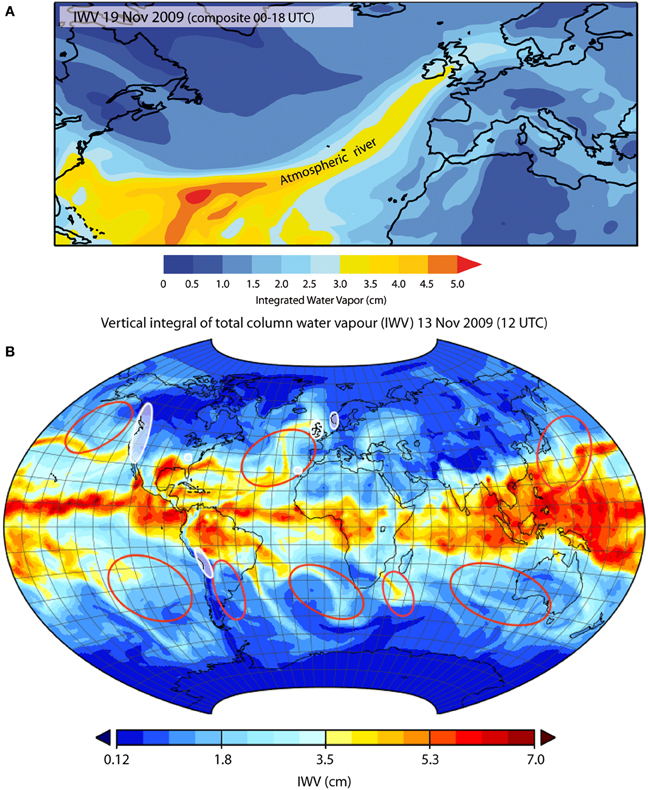

Atmospheric Rivers

Organized moisture transport from warm tropical and subtropical oceans drives a large fraction of midlatitude rainfall.

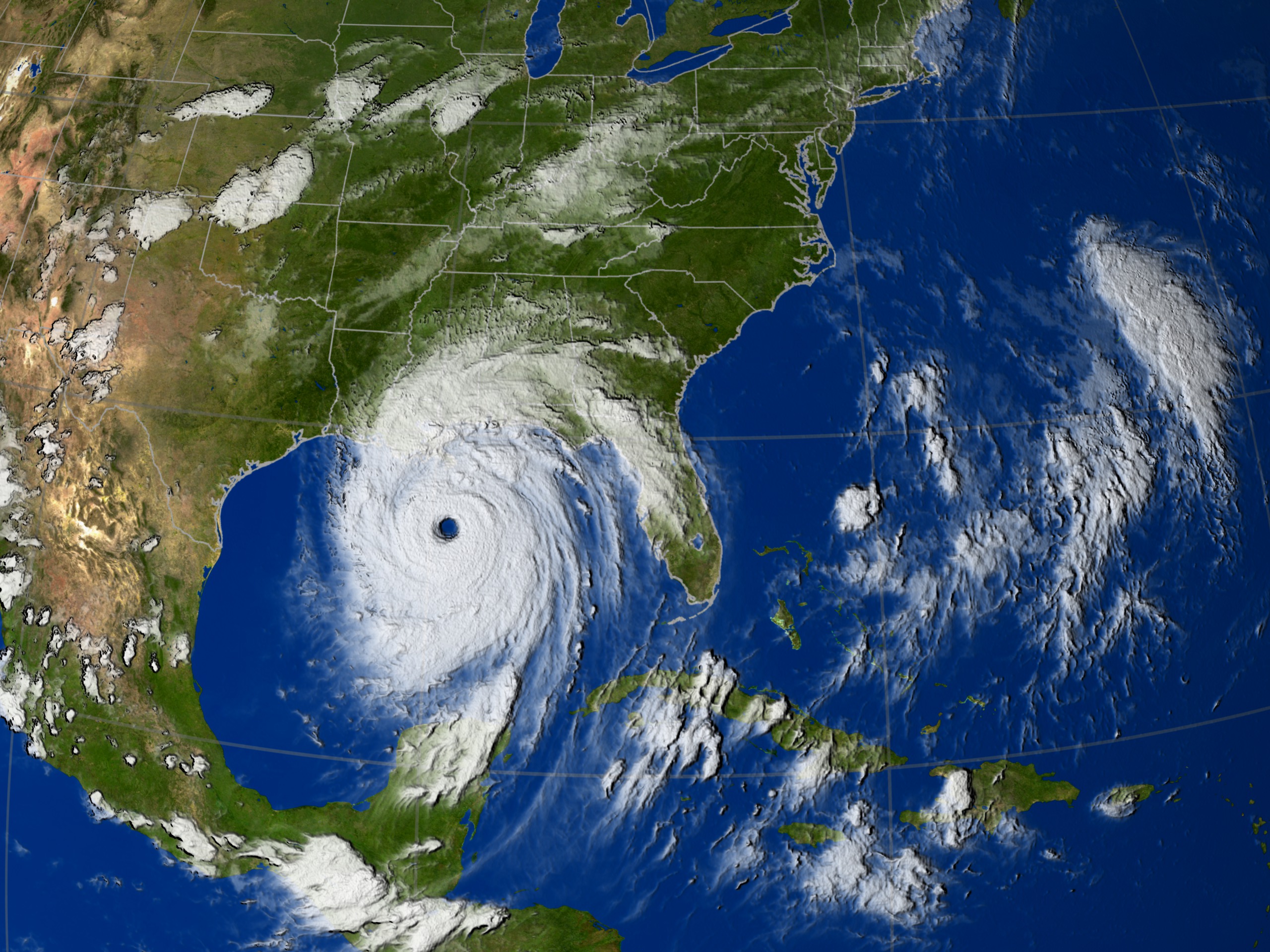

Tropical Cyclones

Organized vortices that convert ocean heat to kinetic energy:

- Require warm SSTs (> 26°C) and low wind shear

- Strongest at landfall → storm surge, wind, rainfall

- Examples: Harvey (2017), Maria (2017), Katrina (2005)

Mesoscale Convective Systems

Organized clusters of thunderstorms (10–100 km):

- Persist longer than individual cells

- Responsible for most warm-season extreme rainfall

- Flash floods, derechos, hail

Blocking Patterns

Persistent high-pressure systems that “block” normal flow:

- Divert the jet stream for days to weeks

- Heat waves (2021 Pacific Northwest, 2003 Europe)

- Can also cause persistent cold (Polar vortex disruptions)

Variability and Persistence

Today

The Climate System

What Generates Extremes?

Variability and Persistence

Models and Their Limits

Sea Level Rise

Wrap Up

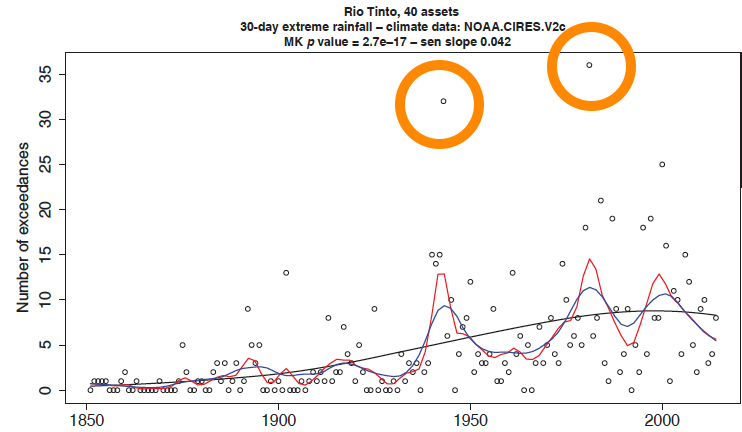

Climate Risks Cluster in Time

Climate extremes are not independent events.

- Droughts persist for years

- Wet periods cluster together

- Hurricane seasons vary dramatically

Climate Risks Cluster in Space

Extremes are spatially correlated.

- Regional droughts affect portfolios

- Flood losses cluster geographically

- Insurance and infrastructure implications

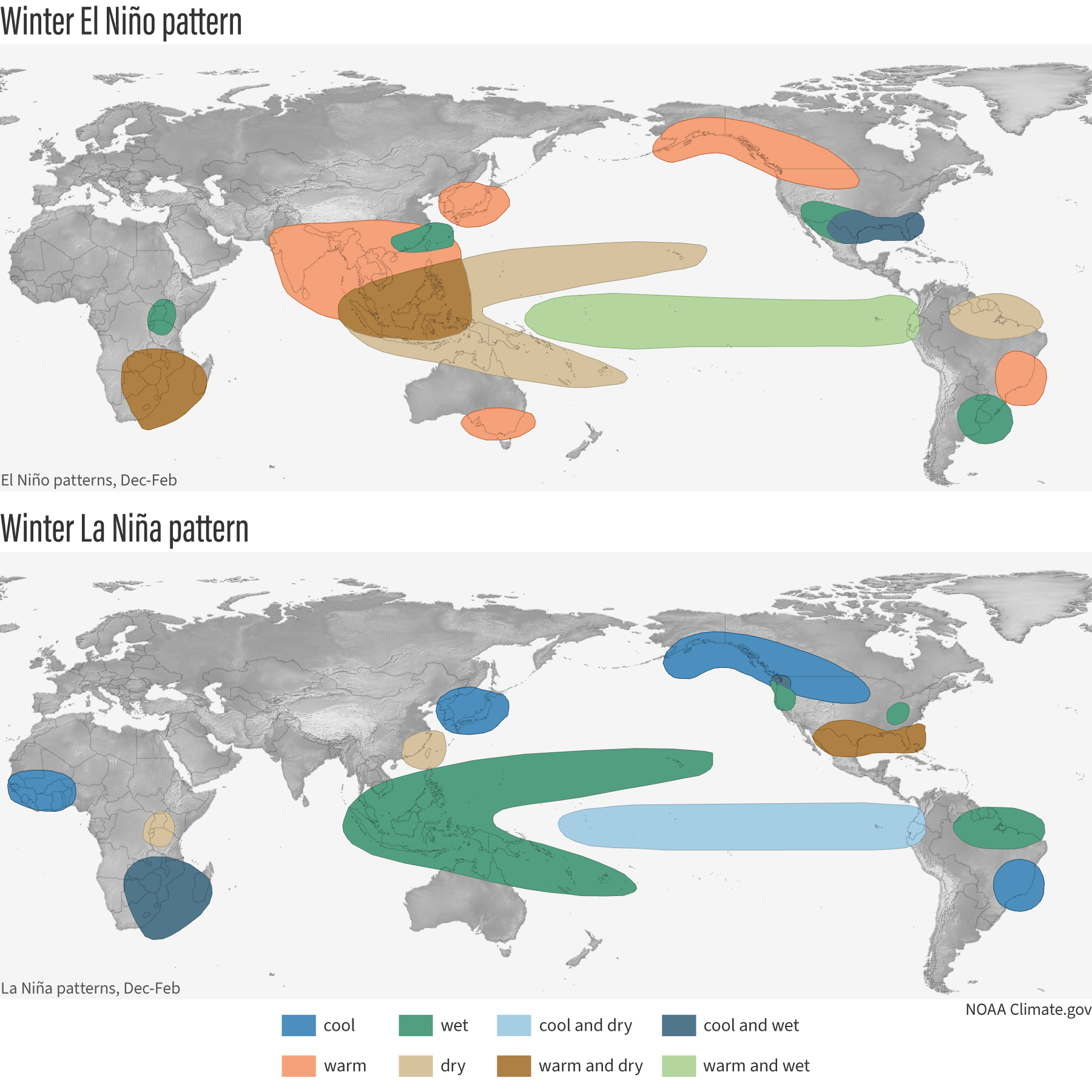

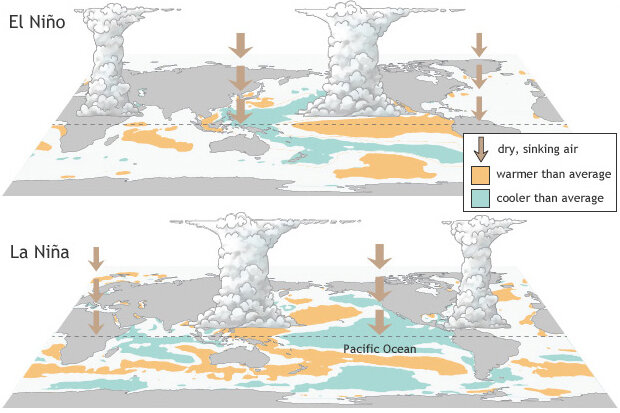

climate.govENSO

The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is the leading mode of variability of the tropical Pacific, with global teleconnections.

climate.govModes of Variability

Large-scale patterns organize climate variability:

- PDO: Pacific Decadal Oscillation (20–30 years)

- NAO: North Atlantic Oscillation

- AMO: Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation

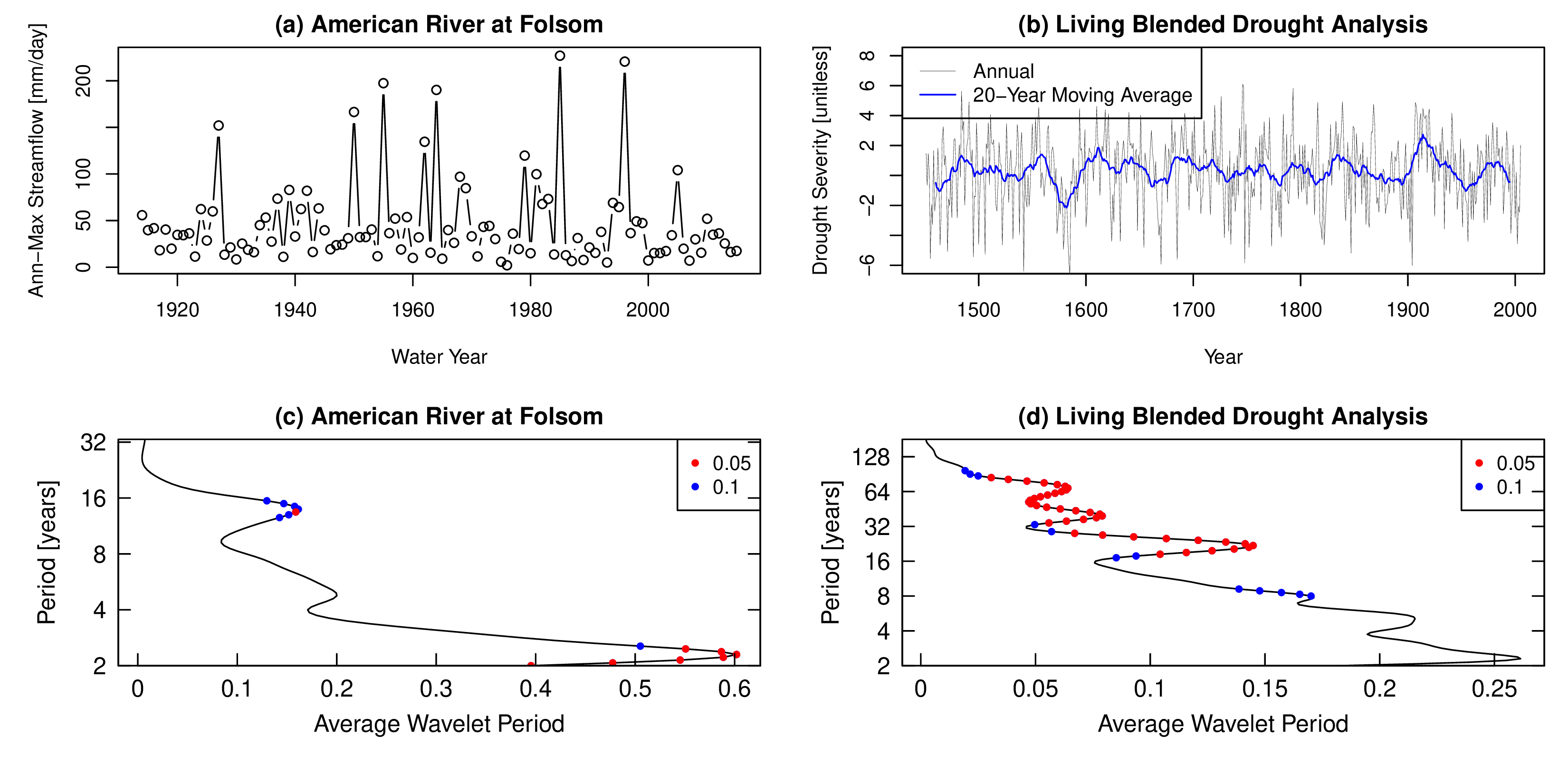

Multiscale Variability

Wavelet analysis reveals variability at multiple timescales. Doss-Gollin et al. (2019)

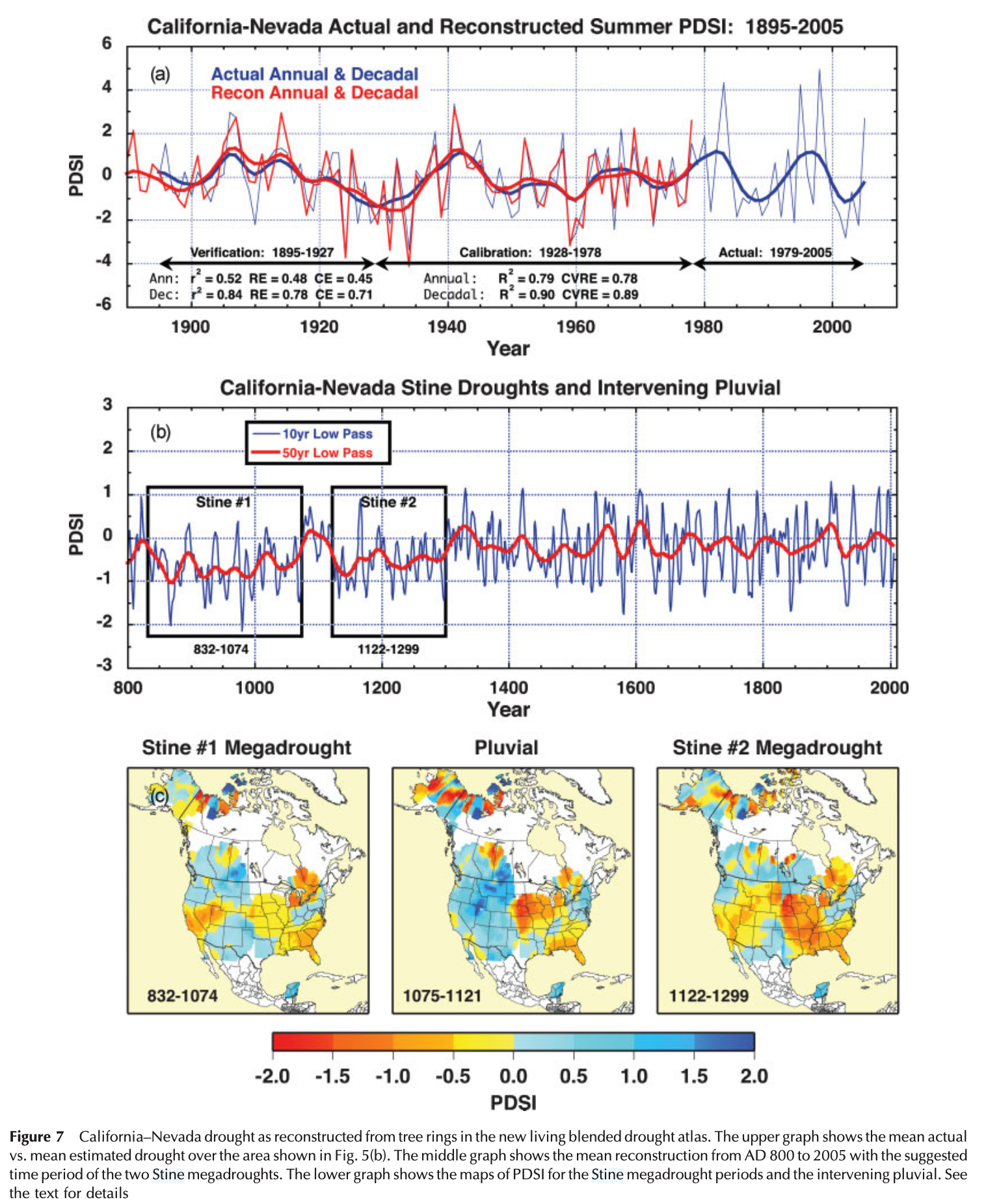

Not just climate change

The paleo record shows:

- Multi-decade droughts occurred without human influence

- The instrumental record (150 years) is a small sample

- Even without climate change, the recent past is a flawed predictor of future hazard.

Models and Their Limits

Today

The Climate System

What Generates Extremes?

Variability and Persistence

Models and Their Limits

Sea Level Rise

Wrap Up

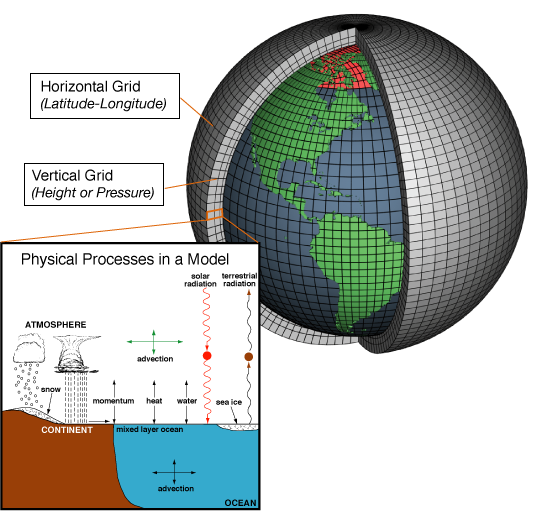

General Circulation Models

General Circulation Models (GCMs) solve physics on a 3D grid:

- Conservation equations for mass, energy, momentum

- Atmosphere, ocean, land, ice components

- Typical resolution: ~100 km grid cells

How GCMs Work

Climate models divide Earth into a 3D grid of cells. Source: NOAA Climate.gov

Resolution Limits

GCMs resolve features larger than ~100 km.

Many hazards are smaller:

| Hazard | Typical Scale |

|---|---|

| Tropical cyclones | ~50 km eye |

| Thunderstorms | ~10 km |

| Tornadoes | ~1 km |

Sub-grid processes must be parameterized, not resolved.

Downscaling

Translating GCM output to local scales:

Statistical Downscaling

- Empirical relationships

- Assumes stationarity of relationships

- Computationally cheap

Dynamical Downscaling

- Higher-resolution physics models

- Computationally expensive

- Inherits GCM biases

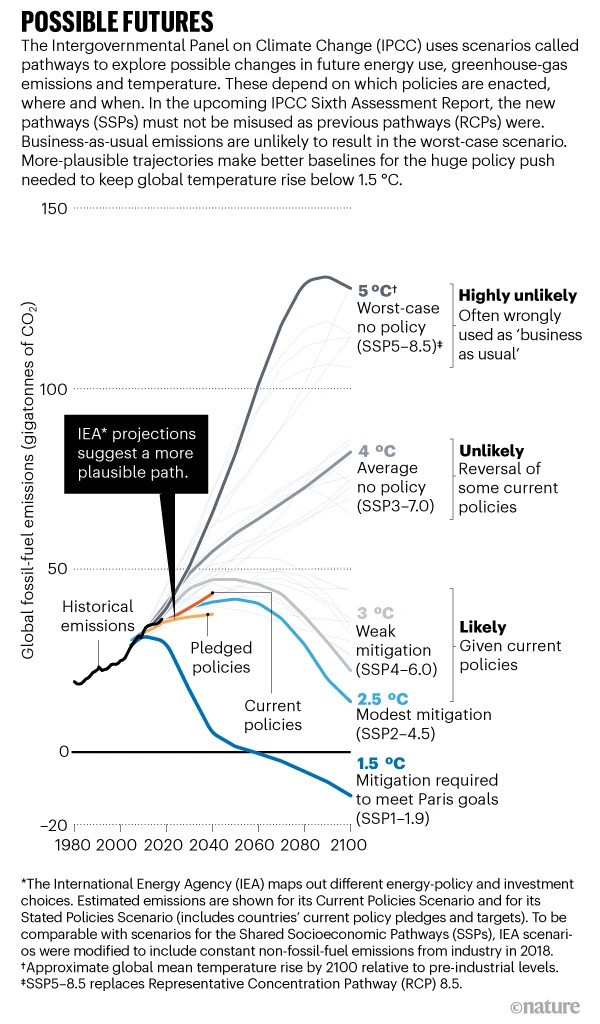

Critical Distinction: Scenarios vs. Projections

| Concept | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Prediction | What WILL happen | Tomorrow’s weather |

| Projection | What WOULD happen IF | Temperature if CO₂ doubles |

| Scenario | Plausible pathway | RCP 8.5 emissions |

Confusing these leads to poor decisions.

Scenarios Are Not Predictions

- Scenarios are “what if” storylines

- They bracket human choices

- No probabilities attached

Sea Level Rise

Today

The Climate System

What Generates Extremes?

Variability and Persistence

Models and Their Limits

Sea Level Rise

Wrap Up

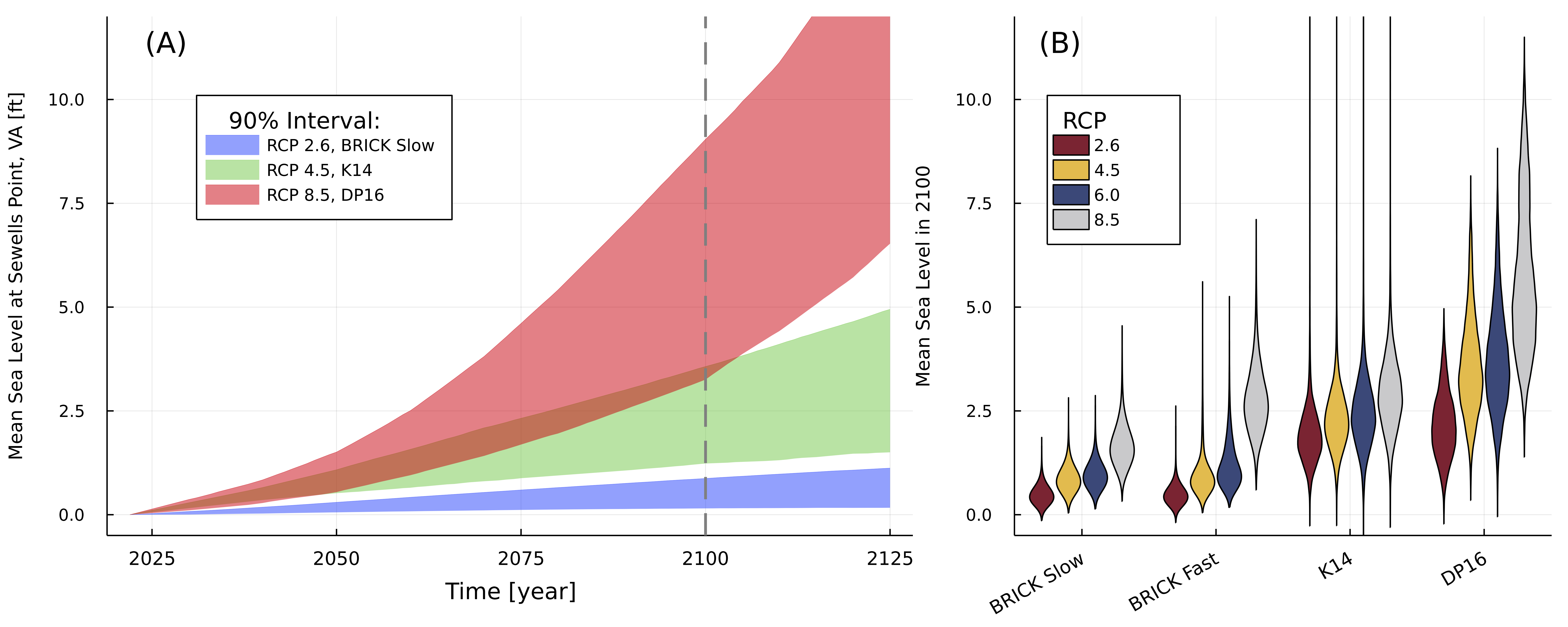

Integrating Case Study

Sea level rise integrates everything we’ve discussed:

- Physical system (thermal expansion, ice dynamics)

- Variability (interannual, decadal)

- Model limitations (ice sheet uncertainty)

- Scenarios vs. projections

Components of Sea Level Rise

Local sea level is affected by multiple processes. Source: NOAA

Two Very Different Sources

Thermal Expansion

- Simple physics (warmer water expands)

- Well-constrained

- Scenario-driven uncertainty

Ice Sheet Melt

- Complex, threshold behaviors

- MISI/MICI processes

- Structural uncertainty dominates

The Ice Sheet Problem

Marine Ice Sheet Instability (MISI) and Marine Ice Cliff Instability (MICI):

- Potential for rapid, irreversible ice loss

- Physical processes are real but poorly constrained

- This is the tail risk for SLR

These processes are the “synoptic generators” of the SLR tail.

Local Factors

Local sea level ≠ global mean:

- Land subsidence: The ground is sinking

- Ocean circulation: Gulf Stream effects

- Gravitational fingerprints: Ice mass redistribution

Wrap Up

Today

The Climate System

What Generates Extremes?

Variability and Persistence

Models and Their Limits

Sea Level Rise

Wrap Up

Key Takeaways

- The System: Climate is chaotic physics; weather ≠ climate

- Synoptic Generators: Extremes come from organized structures

- Variability: Risk clusters in time and space; paleo shows what’s possible

- Model Limits: GCMs are useful but not magic; resolution matters

- Sea Level Rise: Integrates all uncertainties; Lab 3 case study

Looking Ahead

Wednesday: IPCC reading discussion on observed and projected changes

Friday (Lab 3):

- Load NOAA scenarios and BRICK projections for Sewells Point

- Compare scenario uncertainty vs. structural uncertainty

- Ask: Which matters more for the tail?

References

Dr. James Doss-Gollin