Optimal Static Decisions

Lecture

Monday, February 16, 2026

The 1953 North Sea Flood

Today

The 1953 North Sea Flood

van Dantzig’s Simple Model

Adding Realism

Optimization and Policy Search

Evaluating Optimization Claims

February 1, 1953

- 1,800+ people killed

- 150,000 hectares flooded

- 9,000 buildings destroyed

- Economic loss: 1.5–2 billion guilders

The Dutch government forms the Delta Commission. Their charge: make sure this never happens again.

“How High Should We Build the Dikes?”

Historical approach: build to the height of the highest observed flood.

Problem: there is no upper limit to flood height — every height has a positive exceedance probability.

- Higher dikes cost more money to build

- Lower dikes mean more expected flood damage

The question: what is the right height?

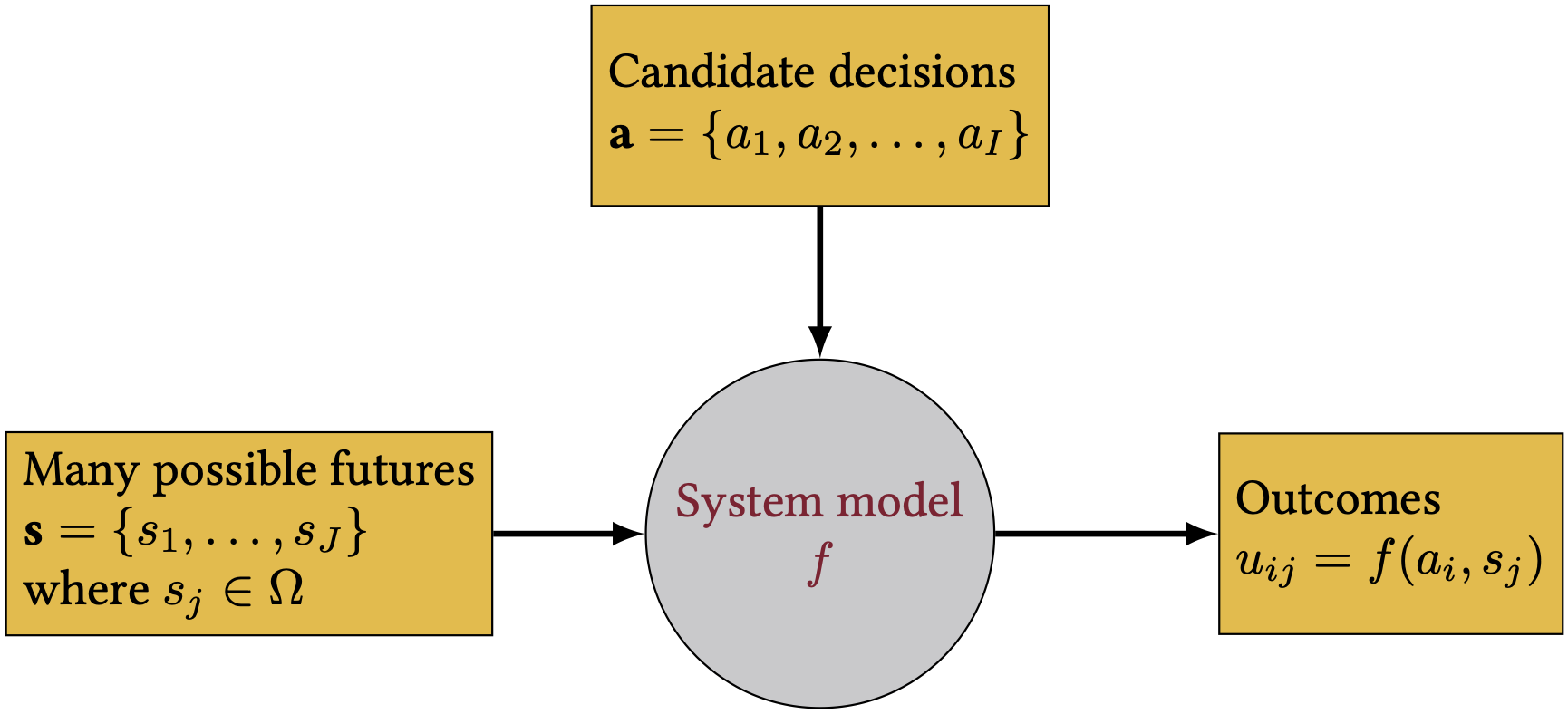

Review: Our System Dynamics Notation

Figure 1: Notation for our system dynamics. Where does optimization fit?

Structure of an Optimization Problem

Every optimization problem has four components:

- Decision variables: What can we control?

- Objective function: What are we trying to minimize or maximize?

- Constraints: What limits our choices?

- Scenarios / states of the world: What uncertainties affect the outcome?

van Dantzig’s Simple Model

Today

The 1953 North Sea Flood

van Dantzig’s Simple Model

Adding Realism

Optimization and Policy Search

Evaluating Optimization Claims

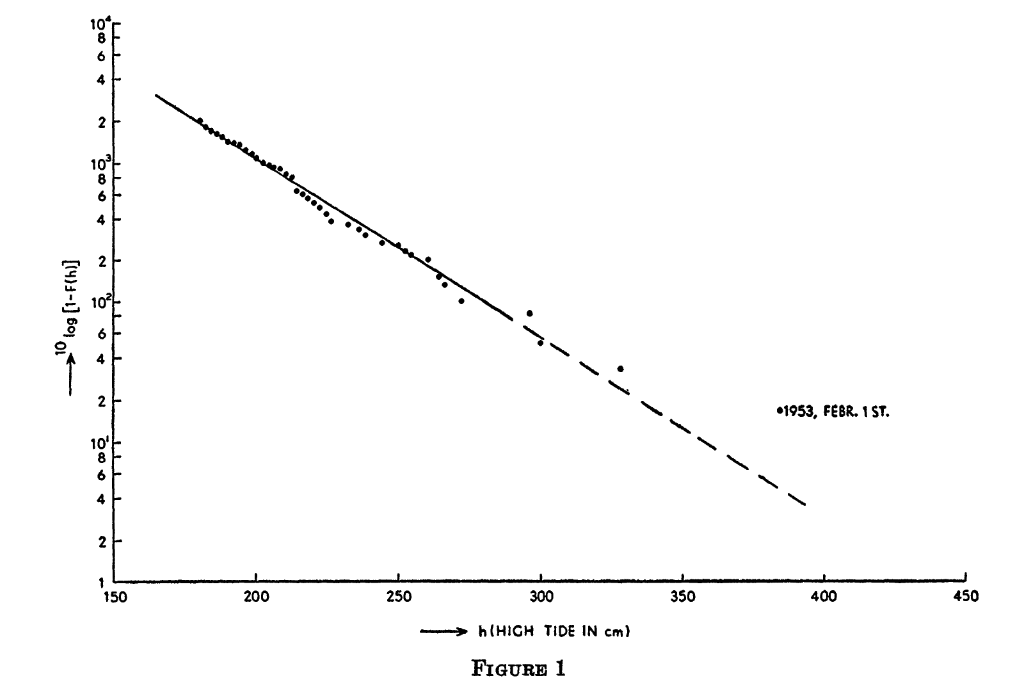

Historical Context

Published in Econometrica, 1956.

Models always trade off realism for tractability — they answer questions and inform decisions, not provide a 1:1 map of the real world.

With no computers available, van Dantzig needed a closed-form solution — so every assumption was chosen to keep the math tractable.

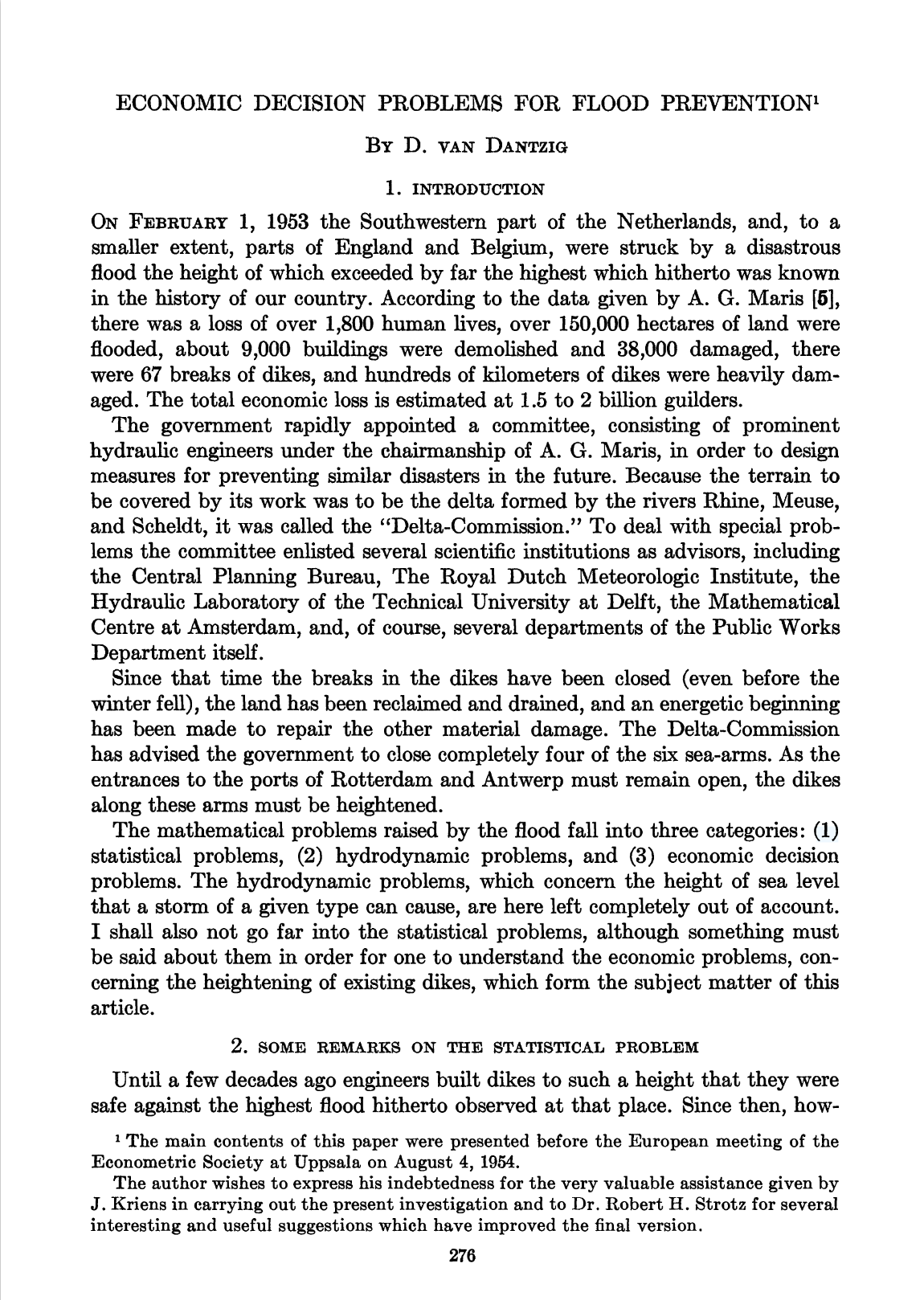

Flood Exceedance Probability

Assumed exponential exceedance probability:

\[ p(h) = p_0 \, e^{-\alpha(h - H_0)} \]

- \(h\) = water height

- \(H_0\) = current dike height

- \(p_0\) = current exceedance probability

- \(\alpha\) = shape parameter

The straight line on the log plot is the exponential fit.

Why exponential? Because it makes the integral tractable.

The Loss Model

van Dantzig assumes binary damage: if water exceeds dike height \(H\), everything in the polder is lost.

\[ S = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if } h \leq H \\ V & \text{if } h > H \end{cases} \]

where \(V\) is the total value of all goods, buildings, farms, cattle, and industry in the polder.

Building the Cost Function

Construction cost (linear approximation): \[I(X) = I_0 + kX\]

Expected annual flood loss (probability \(\times\) total value at risk): \[p_0 \cdot V \cdot e^{-\alpha X}\]

Present value of ALL future expected losses (discounting!): \[L(X) = \frac{100 \, p_0 \, V \, e^{-\alpha X}}{\delta}\]

where \(\delta\) is the interest rate (in percent) — this is NPV, just like Week 5.

The U-Shaped Total Cost

\[ \text{Total}(X) = \underbrace{I_0 + kX}_{\text{construction}} + \underbrace{\frac{100 \, p_0 \, V \, e^{-\alpha X}}{\delta}}_{\text{expected losses (NPV)}} \]

The Analytical Solution

Take the derivative, set equal to zero:

\[ X^* = \frac{1}{\alpha} \ln\!\left(\frac{100 \, p_0 \, V \, \alpha}{\delta \, k}\right) \]

Interpretation:

- Optimal height increases when value \(V\) is high

- Optimal height increases when flood probability \(p_0\) is high

- Optimal height decreases when discount rate \(\delta\) is high

- Optimal height decreases when construction cost \(k\) is high

Adding Realism

Today

The 1953 North Sea Flood

van Dantzig’s Simple Model

Adding Realism

Optimization and Policy Search

Evaluating Optimization Claims

The Netherlands is Changing

Two slow processes push the optimal dike height higher:

Wealth growth: the economy grows at rate \(\gamma\) (estimated 1.5–2.5% per year), so \(V\) increases over time.

Land subsidence: the Netherlands has been sinking for 9,000 years at rate \(\nu\) (~0.7 m/century), so effective dike height decreases.

Both compound over centuries-long planning horizons.

The Reduced Interest Rate

With wealth growth, the effective discount rate becomes:

\[\delta' = \delta - \gamma\]

van Dantzig estimates \(\delta \approx 3.5\text{--}4.5\%\) and \(\gamma \approx 1.5\text{--}2.5\%\), giving \(\delta' \approx 1\text{--}3\%\).

A smaller effective discount rate means future losses matter more — and the optimal dike gets taller.

What happens if \(\gamma \geq \delta\)?

The present value of future losses diverges — there is no finite optimum.

“The Doubtful Constants”

van Dantzig devotes a whole section to parameter uncertainty (Section 6).

Most of his parameters are “rather badly known”:

- \(\alpha\) and \(p_0\) — physical constants, improvable with better data

- \(I_0\) and \(k\) — engineering estimates

- \(V\) — determinable from economic data (with difficulty)

- \(\delta\) and \(\gamma\) — “secular” economic quantities, deeply uncertain over centuries

Which of these can we learn? Which are fundamentally unknowable?

We’ll return to this distinction when we study robustness later in the semester.

The “Safe Side” Approach

van Dantzig’s solution to parameter uncertainty:

“The best thing we can do is to ascertain that our solution will hold under the most unfavourable circumstances which must be considered to be realistic.”

Take the highest reasonable \(p_0\), \(V\), \(\eta\) and the lowest reasonable \(k\), \(\delta'\).

This is a minimax strategy — minimize cost under the worst-case parameter values.

The trade-off: minimax will overdesign relative to the expected case. Choosing to err on the side of safety is defensible — but overdesign has real costs.

We’ll return to robustness more formally in Week 8.

The Numerical Result

The paper considers additional parameters and processes (wealth growth, land subsidence, safe-side estimates) that shift both curves — pushing the optimum higher.

van Dantzig concludes that a dike height of roughly 6 meters “may be considered as a sufficiently safe height.”

This informed the Delta Commission’s decisions — and ultimately the Delta Works.

What About Human Lives?

The 1953 flood killed 1,800 people. Material losses were 1.5–2 billion guilders. At ~100,000 guilders per life lost, the economic framing seems inadequate.

van Dantzig’s approach: look at what the state actually spends to save lives in other domains (railway safety, factory regulations) to derive an implicit value.

“It does not make sense to increase the dikes by an extra centimeter to account for the value of human lives.”

But the dikes should be higher than pure material-loss optimization suggests.

Optimization and Policy Search

Today

The 1953 North Sea Flood

van Dantzig’s Simple Model

Adding Realism

Optimization and Policy Search

Evaluating Optimization Claims

van Dantzig used optimization to inform an engineering design decision. Let’s formalize the general framework.

Optimization Fundamentals

Every optimization problem has the same mathematical structure:

\[ \begin{align} \min_{\mathbf{x}} \quad & f(\mathbf{x}) \\ \text{subject to} \quad & g_j(\mathbf{x}) \leq 0, & j = 1, \ldots, J \\ & h_k(\mathbf{x}) = 0, & k = 1, \ldots, K \end{align} \]

| Notation | Meaning | van Dantzig |

|---|---|---|

| \(\mathbf{x}\) | Decision variables | \(X\) = dike heightening |

| \(f(\mathbf{x})\) | Objective function | Total cost \(I(X) + L(X)\) |

| \(g_j \leq 0\) | Constraints | \(X \geq 0\) |

Stochastic Optimization: How Uncertainty Enters

van Dantzig averaged over flood uncertainty analytically. More generally, when the objective or constraints depend on uncertain quantities \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\):

| Approach | Formulation | Plain English |

|---|---|---|

| Expected value | \(\min_\mathbf{x} \; \mathbb{E}[f(\mathbf{x}, \boldsymbol{\theta})]\) | Minimize the average outcome |

| Chance constraint | \(\Pr[g(\mathbf{x}, \boldsymbol{\theta}) \leq 0] \geq 1 - \epsilon\) | Meet constraints with high probability |

| Robust | \(\min_\mathbf{x} \max_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} f(\mathbf{x}, \boldsymbol{\theta})\) | Minimize the worst case |

van Dantzig used expected value for losses and robust (“safe side”) for parameters — decades before “robust optimization” had a name.

Classes of Optimization Algorithms

The choice of algorithm depends on what structure is available in \(f(\mathbf{x})\):

| Method | What it needs | Strength | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical | Closed form + derivatives | Exact, interpretable | Needs tractable math |

| Linear programming | Linear \(f\) and constraints | Fast, scalable, global optimum | Real problems aren’t linear |

| Gradient descent | Computable \(\nabla f\) | Efficient for smooth problems | Gets stuck in local optima |

| Evolutionary algorithms | Only function evaluations | Handles any black-box model | Slow, no optimality guarantee |

The less structure you can exploit, the more computation you need.

Optimization vs. Policy Search

“Optimization” implies we found THE optimal answer. But it’s only optimal within our model and assumptions.

I prefer the term policy search: using computers to suggest promising alternatives.

- van Dantzig’s answer was optimal — in a model with binary damage and exponential floods

- In practice, a set of good options to evaluate beats a single “optimal” answer

Evaluating Optimization Claims

Today

The 1953 North Sea Flood

van Dantzig’s Simple Model

Adding Realism

Optimization and Policy Search

Evaluating Optimization Claims

Four Key Questions

When someone presents an “optimal” solution:

- Decision variables: What levers are we pulling? What was left out?

- Objective: What are we optimizing? Whose costs and benefits count? What isn’t monetized?

- Constraints: Are these real physical limits or modeling assumptions?

- Scenarios: Over what states of the world is this “optimal”? One scenario, a few, or a full representation of uncertainty?

What’s Next

- Wednesday: Exam 1 (covers Weeks 1–4)

- Friday: Lab 5 — Policy search with ICOW

- Coming up in Module 2: sensitivity analysis, value of information, robustness — all about what happens when your model assumptions are wrong

References

Dr. James Doss-Gollin